Read-along – Anna Karenina (6 of 14)

Part Four, Chapters 1-17 – and Nabokov's double nightmare

Dear Anna Karenina readers,

We’ve finished the sixth monthly instalment of the novel. What a wonderful section! Here are my impressions:

Please do share your thoughts and favourite quotations in the comments below.

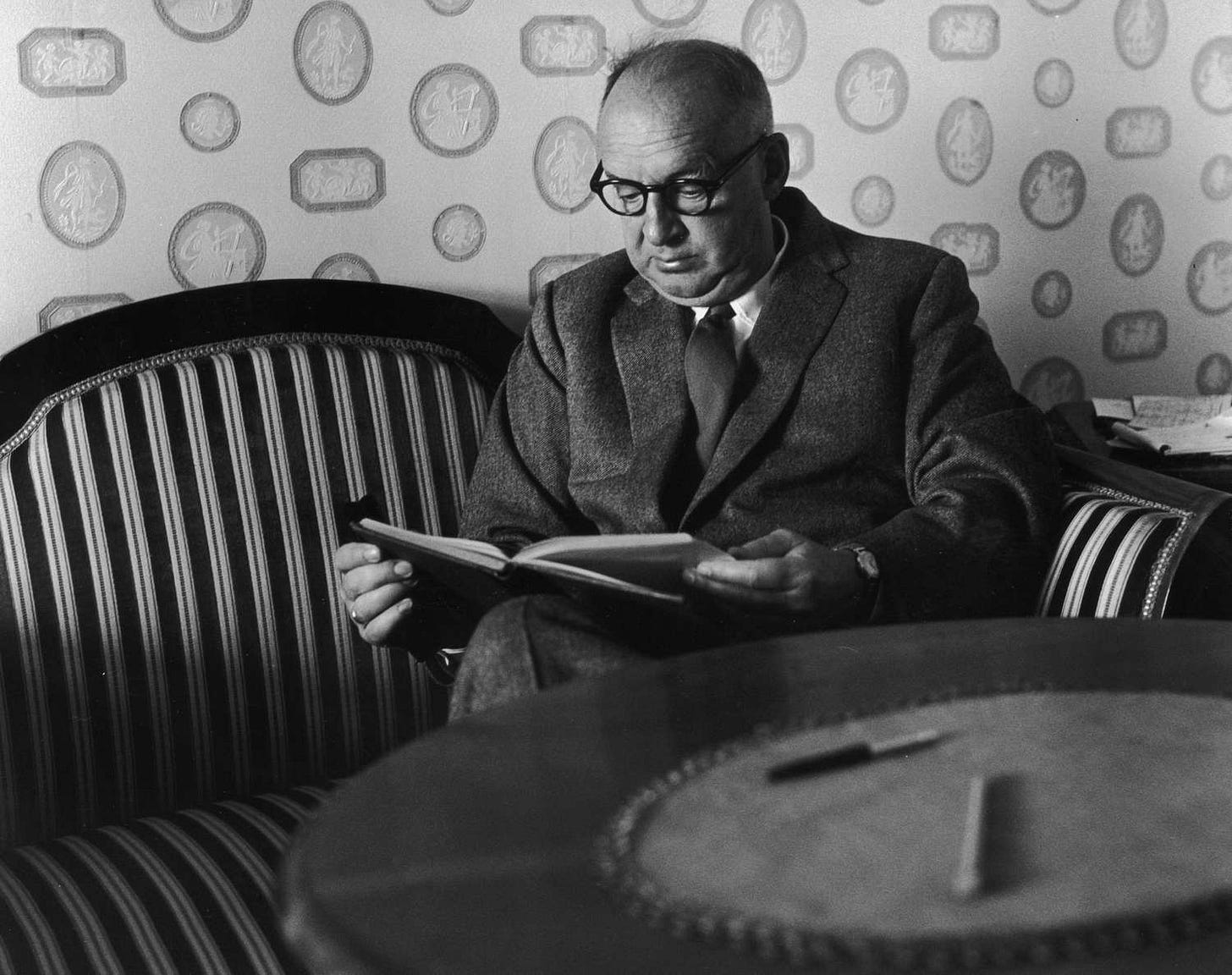

In Vladimir Nabokov’s lecture on Anna Karenina, which we have discussed before, he dwells at length on what he calls ‘The Double Nightmare’, revealing this shared dream as horrifyingly prophetic.

In Part Four, Chapter Two, Vronsky wakes in the dark, trembling with fear:

‘What was that? What? What was the awful thing I dreamed about? Oh, yes. That peasant stalker, I think, who was small and dirty, with a dishevelled beard, was bent over doing something, and suddenly he started saying some strange words in French. No, there was nothing else in the dream,’ he said to himself. ‘But why was it so awful then?’ He vividly recalled the peasant again and the incomprehensible French words the peasant had been uttering, and a chill of horror ran down his spine.

Then in the next chapter we learn that Anna has had a similar dream:

‘Yes a dream,’ she said. ‘I had this dream a long time ago. I dreamed that I ran into my bedroom because I needed to get something or find something out; you know what it is like when you are dreaming,’ she said, opening her eyes wide in horror; ‘and in the bedroom, in the corner, there was something standing there.’

‘Oh, what nonsense! How can you believe . . . ’

But she would not let him interrupt her. What she was saying was too important to her.

‘And this something turned round, and I saw it was a small peasant with a dishevelled beard and very frightening. I wanted to run away, but he was bent over a sack, and was rummaging about in it with his hands . . . ’

She showed how he had rummaged in the sack. There was horror in her face. And Vronsky felt the same horror filling his soul as he remembered his dream.

‘He was rummaging and saying in French, very quickly, and, you know, rolling his r’s like the French: Il faut le battre le fer, le broyer, le pétrir . . . [‘the iron must be beaten, pounded, shaped . . .’] And I was so scared I wanted to wake up, and I did wake up . . . but I woke up in a dream. And I began asking myself what it meant. And Korney tells me: “You’ll die in childbirth, ma’am, in childbirth . . . ” And I woke up . . . ’

Something about this nightmare reminds me of the dream sequence from the first season of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks (1990):

This is what Nabokov has to say about Anna and Vronsky’s double dream:

A dream, a nightmare, a double nightmare plays an especially important part in the book. I say ‘double nightmare’ because both Anna and Vronsky see the same dream. (This monogrammatic interconnection of two individual brain-patterns is not unknown in so-called real life.) You will also mark that Anna and Vronsky, in that flash of telepathy, undergo technically the same experience as Kitty and Levin do when reading each other’s thoughts as they chalk initial letters on the green cloth of a card table. But in Kitty-Levin’s case the brain-bridge is a light and luminous and lovely structure leading towards vistas of tenderness and fond duties and profound bliss. In the Anna and Vronsky case, however, the link is an oppressive and hideous nightmare with dreadful prophetic implications.

As some of you may have guessed, I am politely but firmly opposed to the Freudian interpretation of dreams with its stress on symbols which may have some reality in the Viennese doctor’s rather drab and pedantic mind but do not necessarily have any in the minds of individuals unconditioned by modern psychoanalytics. Hence I am going to discuss the nightmare theme of our book, in terms of the book, in terms of Tolstoy’s literary art. [. . .]

So let us start by studying the ingredients of the double nightmare, Anna’s and Vronsky’s. What do I mean by the ingredients of a dream? Let me make this quite clear. A dream is a show—a theatrical piece staged within the brain in a subdued light before a somewhat muddleheaded audience. The show is generally a very mediocre one, carelessly performed, with amateur actors and haphazard props and a wobbly backdrop. But what interests us for the moment about our dreams is that the actors and the props and the various parts of the setting are borrowed by the dream producer from our conscious life. A number of recent impressions and a few older ones are more or less carelessly and hastily mixed on the dim stage of our dreams. Now and then the waking mind discovers a pattern of sense in last night’s dream; and if this pattern is very striking or somehow coincides with our conscious emotions at their deepest, then the dream may be held together and repeated, the show may run several times as it does in Anna’s case.

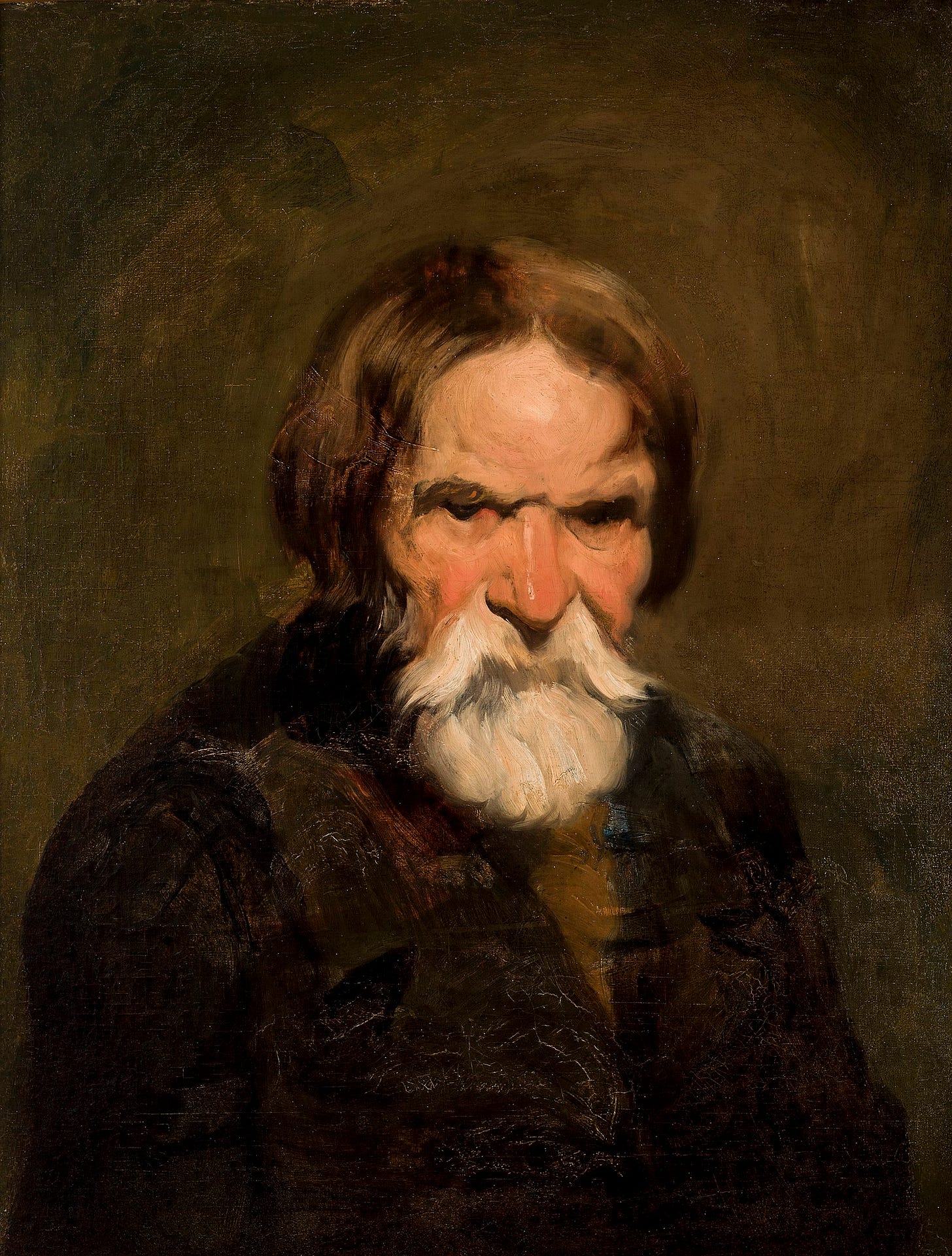

What are the impressions a dream collects on its stage? They are obviously filched from our waking life, although twisted and combined into new shapes by the experimental producer, who is not necessarily an entertainer from Vienna. In Anna and Vronsky’s case the nightmare takes the form of a dreadful-looking little man, with a bedraggled beard, bending over a sack, groping in it for something, and talking in French—though he is a Russian proletarian in appearance—about having to beat iron. [. . .] Let us compare Anna’s dream and Vronsky’s dream.

They are essentially the same of course and both are founded in the long run on those initial railway impressions a year and a half before—on the railway guard crushed by a train. But in Vronsky’s case the initial tattered wretch is replaced, or let us say acted, by a peasant, a trapper, who had participated in a bear hunt. In Anna’s dream there are added impressions from her railway journey to Petersburg— the conductor, the stove-tender. In both dreams the hideous little peasant has a disheveled beard, and a groping, fumbling manner—remnants of the ‘muffled-up’ idea. In both dreams he stoops over something and mutters something in French—the French patter they both used in speaking of everyday things in what Tolstoy considered a sham world; but Vronsky does not catch the sense of those words; Anna does, and what these French words contain is the idea of iron, of something battered and crushed—and this something is she.

You can read Nabokov’s full lecture here, although beware of spoilers.

I hope you enjoy the next instalment of Anna Karenina. On 25th July we will discuss Part Four, Chapters 8-23 and Part Five, Chapters 1-6. These chapters formed the seventh instalment of the novel, first published in the Russian Messenger in March 1876.

For reference, here are links to our previous Anna Karenina posts:

The Schedule (18 December 2024)

Leo Tolstoy (3 January 2025)

0. Introductions (10 January)

1. Part One, Chapters 1-23 – and Nabokov on Time (31 January)

2. Part One, Chapters 24-34, Part Two, Chapters 1-11 – and John Sutherland on Anna’s English novel (28 February)

3. Part Two, Chapters 12-29 – and Sergei Eisenstein at the races (28 March)

4. Part Two, Chapters 30-35, Part Three, Chapters 1-12 – and the Mowing Scene (25 April)

5. Part Three, Chapters 13-32 – and the Mirror of the Revolution (30 May)

And if you’re not reading Anna Karenina with us, remember you can choose to opt out of our conversation. Just follow this link to your settings and, under Notifications, slide the toggle next to ‘Anna Karenina’. A grey toggle means you will not receive emails relating to this title.

Henry, I agree with others that your video mini-lectures really elevate your read-alongs. You're teaching me by example to read more vigorously, to appreciate more deeply. I'll read a passage and think it's good -- good plot movement, good characterizations, good descriptions -- but then your expressions of joy over the greatness of those same passages shows me how much more there is. I'm slowly, slowly learning to read with your zeal. Thank you for setting that example.

A restaurant critic friend used to refer to her guest for a meal she was reviewing as her "convive." I just looked it up again, and, unlike "convivial," it's used narrowly in food-related settings. That's how I've come to think of you -- as our convive, showing us we're at a banquet with so much to savor.

Such excitement! Such turmoil! You're right, Henry, that we as readers are quite confused over the change in the Karenin-Anna-Vronsky triangle. Anna seems to also have had a change of heart, but is it all just hormone-related guilt? Childbirth is a big deal. What will happen to the baby? Who will raise her and who will she think her father is? What a cliffhanger.

I found the women's lib discussion infuriating (as an American woman in 2025) but was pleased at the Pestov character. Related: I have noticed that Levin is easily swayed on things. His viewpoints are quite malleable, which is good, I think, but it also makes me think he hasn't done a whole lot of critical thinking on some of these topics.

The government committee scenes were pretty funny - the whole thing felt a bit like a farce. Tolstoy is painting the government bureaucrats as a bunch of paper-pushers.