Read-along – Anna Karenina (5 of 14)

Part Three, Chapters 13-32 – and the Mirror of the Revolution

Dear Anna Karenina readers,

We’ve finished the fifth instalment! Here’s what I made of it:

Please do share your thoughts and favourite quotations in the comments below.

In this section, Levin devises a new method of farming: he gives his workers a share of the profits, so they’ll be motivated to work harder and more efficiently. In other words, his farm becomes a collective. He has a vision of

a bloodless revolution, but a mighty revolution, at first in the small confines of our district, then the province, Russia, and the whole world. Because a valid idea cannot fail to bear fruit.

He is an idealist, confident that if he pursues his new idea, he will overcome resistance and any practical complications and ultimately create a better future.

Perhaps, then, it’s no surprise that, thirty years later, another idealistic Russian admired Tolstoy’s writing.

On 28 August 1908, Leo Tolstoy turned 80. (For most of the rest of the world, his birthday fell on 9 September, but Russia continued to use the Julian calendar until 1918, by which time Tolstoy was dead.)

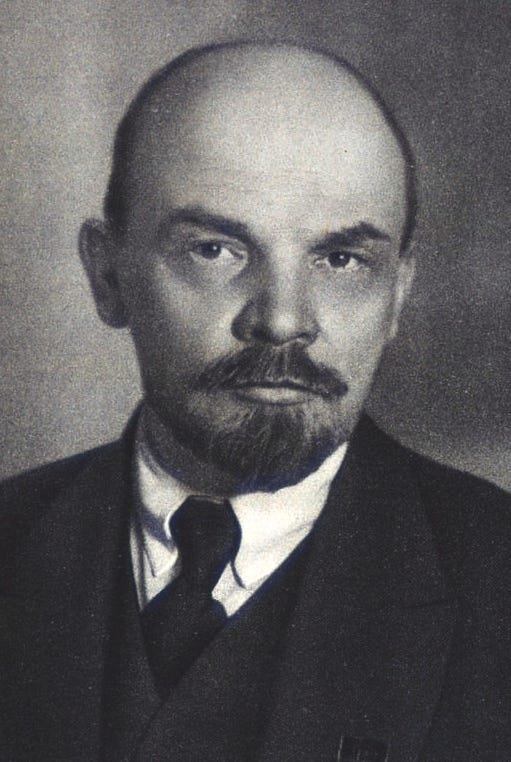

In Russia there was a national celebration of the great author, and a few days later Vladimir Lenin, in Switzerland, published an article in the magazine Proletary called ‘Leo Tolstoy as the Mirror of the Russian Revolution’. You can read the full article here.

Lenin starts by pointing out that Tolstoy had never openly supported a Russian Revolution, but then he recommends a closer reading of Tolstoy’s works:

Tolstoy’s views are indeed a mirror of those contradictory conditions in which the peasantry had to play their historical part in our revolution. . . . Centuries of feudal oppression and decades of accelerated post-Reform pauperisation piled up mountains of hate, resentment, and desperate determination. The striving to sweep away completely the official church, the landlords and the landlord government, to destroy all the old forms and ways of landownership, to clear the land, to replace the police-class state by a community of free and equal small peasants – this striving is the keynote of every historical step the peasantry has taken in our revolution; and, undoubtedly, the message of Tolstoy’s writings conforms to this peasant striving far more than it does to abstract ‘Christian Anarchism’, as his ‘system’ of views is sometimes appraised.

He goes on to say, however, that the contradictions in Tolstoy’s position explain both the Russians’ desire for revolution and their lack of success so far:

Tolstoy reflected the pent-up hatred, the ripened striving for a better lot, the desire to get rid of the past – and also the immature dreaming, the political inexperience, the revolutionary flabbiness. Historical and economic conditions explain both the inevitable beginning of the revolutionary struggle of the masses and their unpreparedness for the struggle, their Tolstoyan non-resistance to evil, which was a most serious cause of the defeat of the first revolutionary campaign.

And he ends by looking beyond Tolstoy, as a voice of the past, and forward to a glorious future for the revolution:

Among the peasantry themselves the growth of exchange, of the rule of the market and the power of money is steadily ousting old-fashioned patriarchalism and the patriarchal Tolstoyan ideology. . . . The lines of demarcation have become more distinct. The cleavage of classes and parties has taken place. Under the hammer blows of the lessons taught by Stolypin, and with undeviating and consistent agitation by the revolutionary Social-Democrats not only the socialist proletariat but also the democratic masses of the peasantry will inevitably advance from their midst more and more steeled, fighters who will be less capable of falling into our historical sin of Tolstoyism!

Within ten years, of course, Tolstoy was dead and Lenin was swept to power in the October Revolution of 1917 and so began seventy-four years of Soviet Russia.

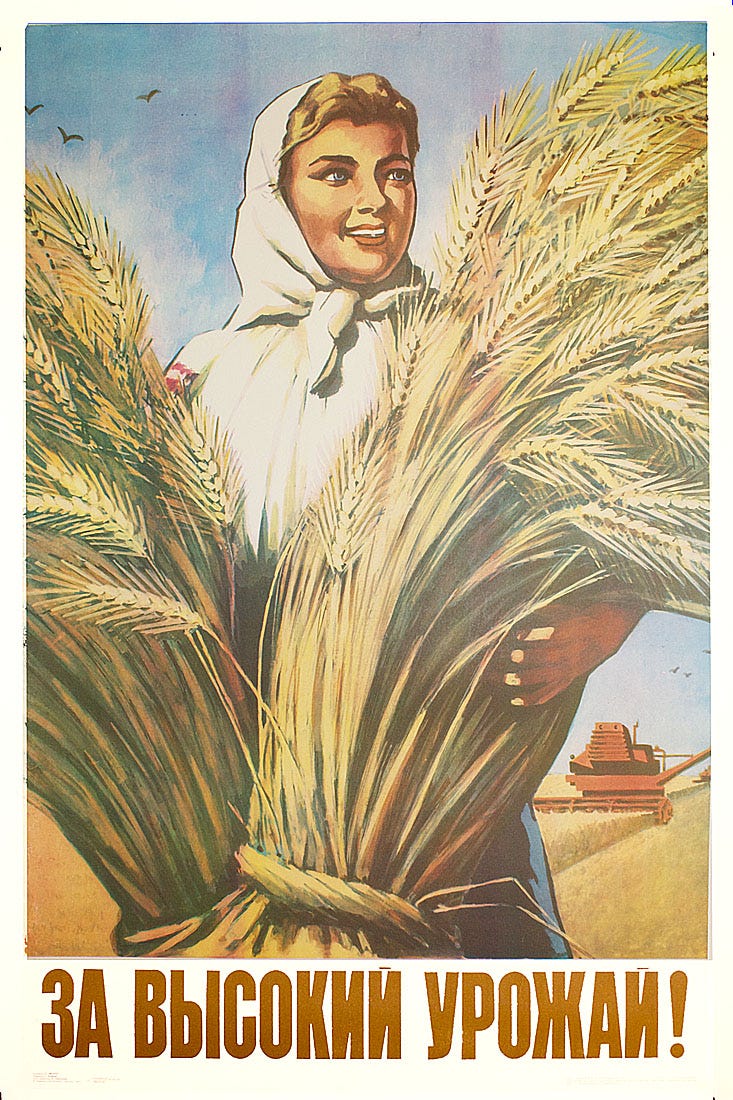

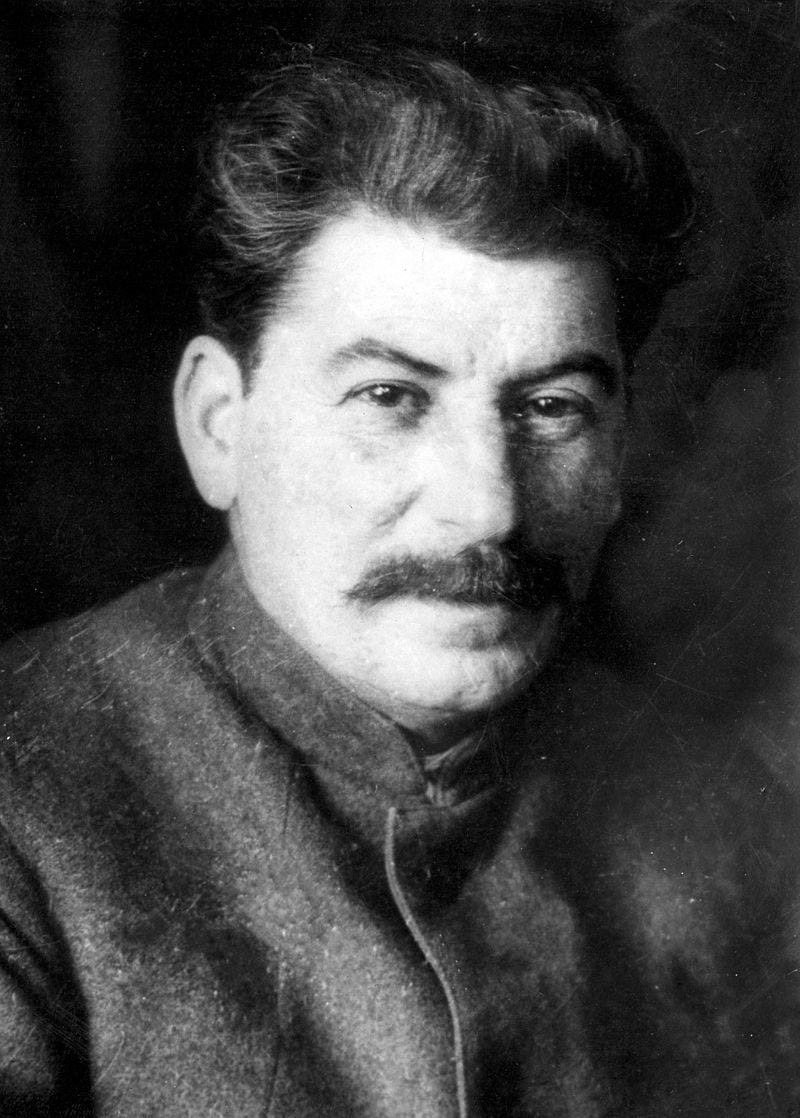

Then, in the late 1920s, Levin’s idealistic vision for his farm was nightmarishly paralleled in the real world, when Stalin introduced forced collectivisation as part of the ‘five-year plan’.

The idea was to improve agricultural production by organising labour on collective farms (kolkhozy) and at the same time liberate peasants by giving them a share of ownership and profits. The idea was satirised by George Orwell, of course, in Animal Farm (1945).

It was a disaster. In order to implement his plans, Stalin resorted to mass executions and deportations of Russia’s land-owning class (kulaks) and his extreme measures triggered the ‘Soviet Famine’ of 1930-1933.

In the year 1932-33 alone, an estimated 11 million people died from famine as a result of being forced into farming collectives.

Despite technological advances, agricultural production did not exceed pre-collectivisation levels until 1940.

I hope you enjoy the next instalment of Anna Karenina. On 27th June we will discuss Part Four, Chapters 1-17. These chapters formed the sixth instalment of the novel, first published in the Russian Messenger in February 1876.

For reference, here are links to our previous Anna Karenina posts:

The Schedule (18 December 2024)

Leo Tolstoy (3 January 2025)

0. Introductions (10 January)

1. Part One, Chapters 1-23 – and Nabokov on Time (31 January)

2. Part One, Chapters 24-34, Part Two, Chapters 1-11 – and John Sutherland on Anna’s English novel (28 February)

3. Part Two, Chapters 12-29 – and Sergei Eisenstein at the races (28 March)

4. Part Two, Chapters 30-35, Part Three, Chapters 1-12 – and the Mowing Scene (25 April)

And if you’re not reading Anna Karenina with us, remember you can choose to opt out of our conversation. Just follow this link to your settings and, under Notifications, slide the toggle next to ‘Anna Karenina’. A grey toggle means you will not receive emails relating to this title.

I had a bit of an epiphany reading this section - although I am probably just late to the party and everyone else realised this ages ago! I've always assumed that the opening lines of 'Anna Karenina' referred to Anna and her family, but it does actually refer to all the families involved: Levin and Nikolai, Dolly and Stepan, Kitty and her family as well as Anna and Karenin - they all have their own individual ways of making their lives miserable. (Regular readers of my ramblings can take the Ira Gershwin quotation as read.)

In compare and contrast mode, I thought about how different Anna's experience is from Masha in 'Three Sisters' where her husband seems to understand her situation but does not reproach her and wants to build bridges. (Not to mention Ibsen's 'Lady From The Sea' where giving Ellida her freedom makes her decide to stay. Karenin could learn a lot from them.

Levin is starting to become my favourite character. (Maybe I recognise a fellow over-thinker in him.) He wants to be better, to do better - but forgets that he needs to take people along with him. I recognise that in me as well. His pessimism, though, is a bit wearing - even when he makes improvements, he focuses on the problems not the successes.

I was amused by the 'don't look at the cleavage! God, I'm looking at the cleavage' section. Having previously invoked Chekhov and Ibsen, this was making me think of 'Carry On'!

I saw something (possibly on Substack) along the lines 'Anna Karenina' is the wrong title for the book and, unfortunately, mislaid it before I had time to read it. I think I can see where the article was coming from: although Anna and Vronsky set off a lot of the action, we are as invested in Dolly, Kitty, Levin and Stepan. Invested in, but also feeling each of them could benefit from a damned good talking-to!

I was warned that vast portions of this novel were about “tedious farming”. However, I love Levin on his estate and his striving to make agriculture more productive.

It may be that I am old now but it’s every bit as fascinating as Anna and her tortured love affair. I don’t think the novel would work half so well without either half of the story.