Dear Anna Karenina readers,

I’m really looking forward to our fourteen-month Anna Karenina read-along adventure, which begins next Friday 10 January. All the details are here.

In the meantime, here’s a short biography of Tolstoy before we get started.

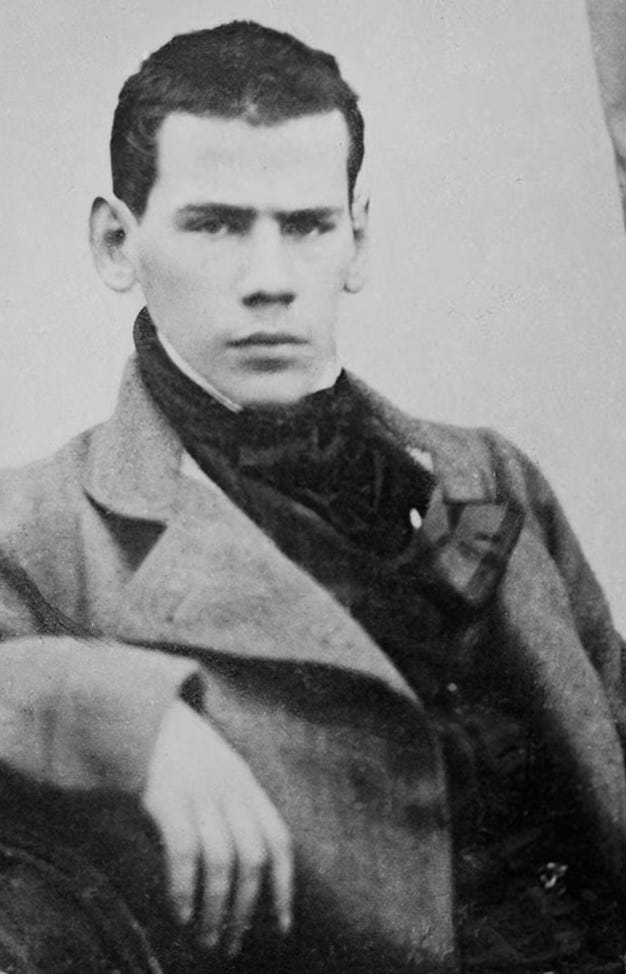

Leo Tolstoy was born into an aristocratic Russian family. His father Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy had fought against the French during Napoleon’s 1812 invasion, the campaign that Tolstoy would later recreate in War and Peace.

As a young man, Tolstoy led a dissipated life of gambling, drinking and womanizing. He joined an artillery regiment in 1851 and fought in the Crimean War, an experience that inspired his three Sevastapol Stories (1855), set during the Siege of Sevastapol. In 1856, however, he resigned his commission and returned to his birthplace, his vast family estate at Yasnaya Polyana, 125 miles south of Moscow. He spent the rest of his life there.

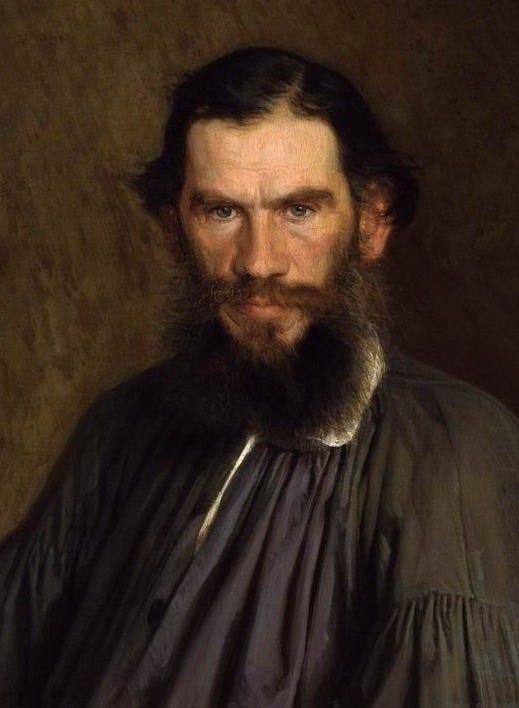

He married Sofya Behrs in 1862 and they had thirteen children over fifteen years. He studied various theories of education and established an innovative school for peasant children on the estate. He became increasingly famous for his stories, novellas and political writings and he produced two of the greatest novels ever written. The first was War and Peace, his epic evocation of Russia’s Napoleonic wars, published in 1869. It features almost 600 characters, from aristocrats to peasants, landowners, soldiers and even Napoleon himself. Ivan Goncharov considered War and Peace the Russian Iliad.

Tolstoy’s second great masterpiece was Anna Karenina, serialised between 1875 and 1877 and published as a book in 1878. In this novel, the landowner Konstantin Levin toils alongside his estate workers and pines for Anna Karenina’s sister-in-law, Princess Kitty. Levin is in many ways a self-portrait of Tolstoy himself.

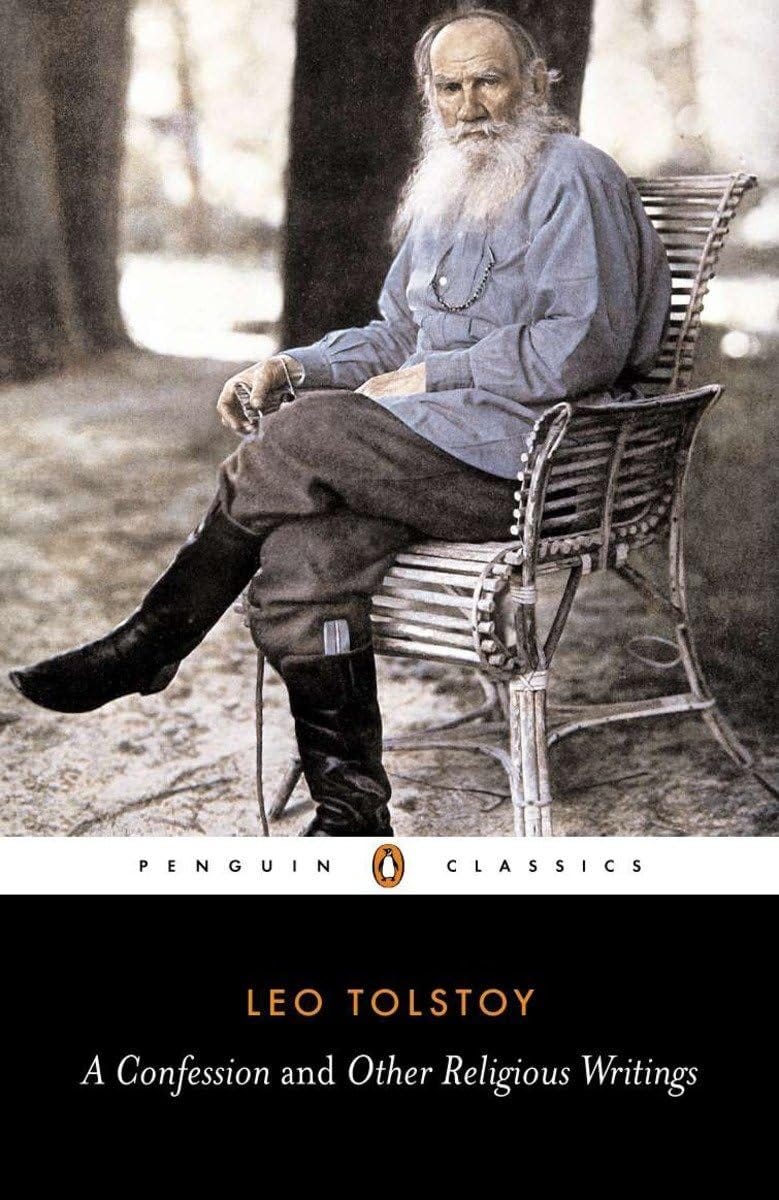

In the late 1870s Tolstoy experienced a spiritual crisis, which he described in his Confession (written 1879-80). He began to turn away from literature and sought instead ‘a practical religion not promising future bliss but giving bliss on earth’. He became an extreme rationalist and was officially excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox Church.

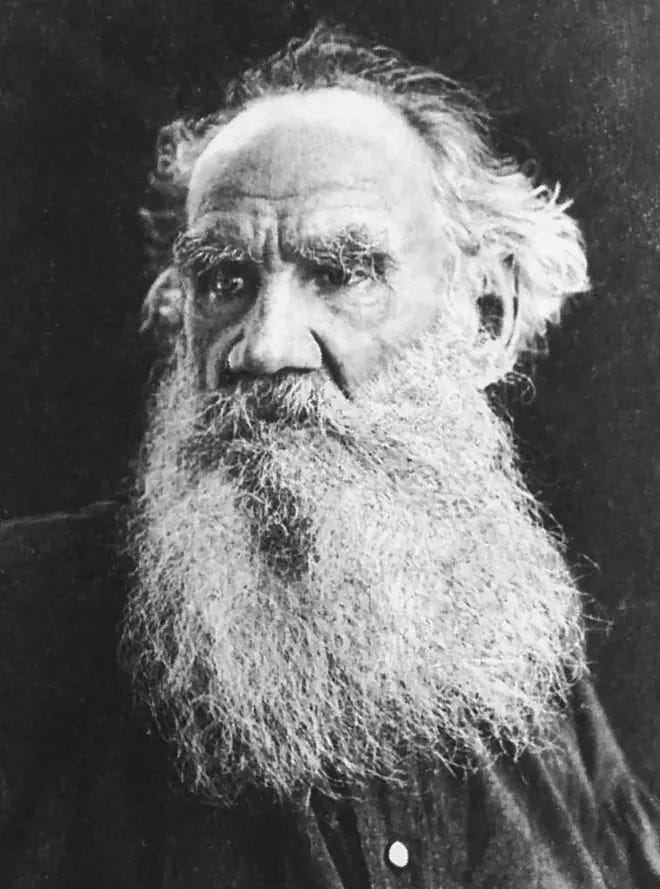

At the age of 82, oppressed by his international reputation and alienated from his wife, he fled his home in the middle of the night ‘in order to live out my last days in peace and solitude’. He died within a week, in the small railway station of Astapovo.

Many agree with Virginia Woolf, who considered Tolstoy the greatest of all novelists. ‘When literature possesses a Tolstoy,’ wrote Chekhov, ‘it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be, because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature.’

If you’re not planning to read Anna Karenina with us, you can choose to opt out of our Leo Tolstoy conversation. Just follow this link to your settings and, under Notifications, slide the toggle next to ‘Anna Karenina’. A grey toggle means you will not receive emails relating to this title.

When I was in my twenties I read with great care and attention ‘War and Peace’ and it remains one of my greatest reading experiences. In those time rich days I even kept a notebook to help me stay up to speed with all the characters and their connections. Now, in my fifties, with your wonderful project Henry, I can finally get to grips with this other great work. The only thing I really know about it is the truth of its famous opening line.

I just finished War and Peace and can’t wait to dig back into Anna K.