Read-along – The Old Curiosity Shop (6 of 18)

Master Humphrey's Clock No.6 – and St. Dunstan-in-the-West

Dear Old Curiosity Shop readers,

We’ve read the sixth issue of Master Humphrey’s Clock, which concluded Mr Pickwick’s story and introduced another old friend from The Pickwick Papers – Sam Weller. What did you think? Please do share your thoughts in the comments below. Here are my impressions:

Here are the details of the next instalment:

No.7 (16 May)

There were two items in the seventh issue of Master Humphrey’s Clock:

– ‘The Clock’

– ‘The Old Curiosity Shop, Chapter the Second’

Finally we can read the second chapter of The Old Curiosity Shop! (If you don’t have a physical copy of Master Humphrey’s Clock you can read ‘The Clock’ here. Stop before ‘Mr. Weller’s Watch’.)

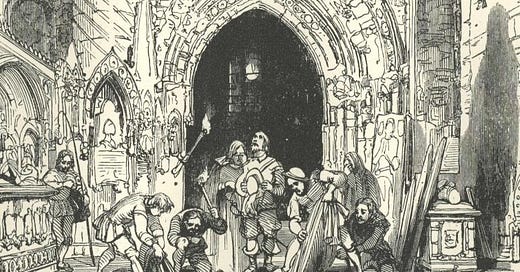

In Mr. Pickwick’s tale, Will Marks is persuaded to convey the corpse of the executed man to ‘the Church of St. Dunstan in London’.

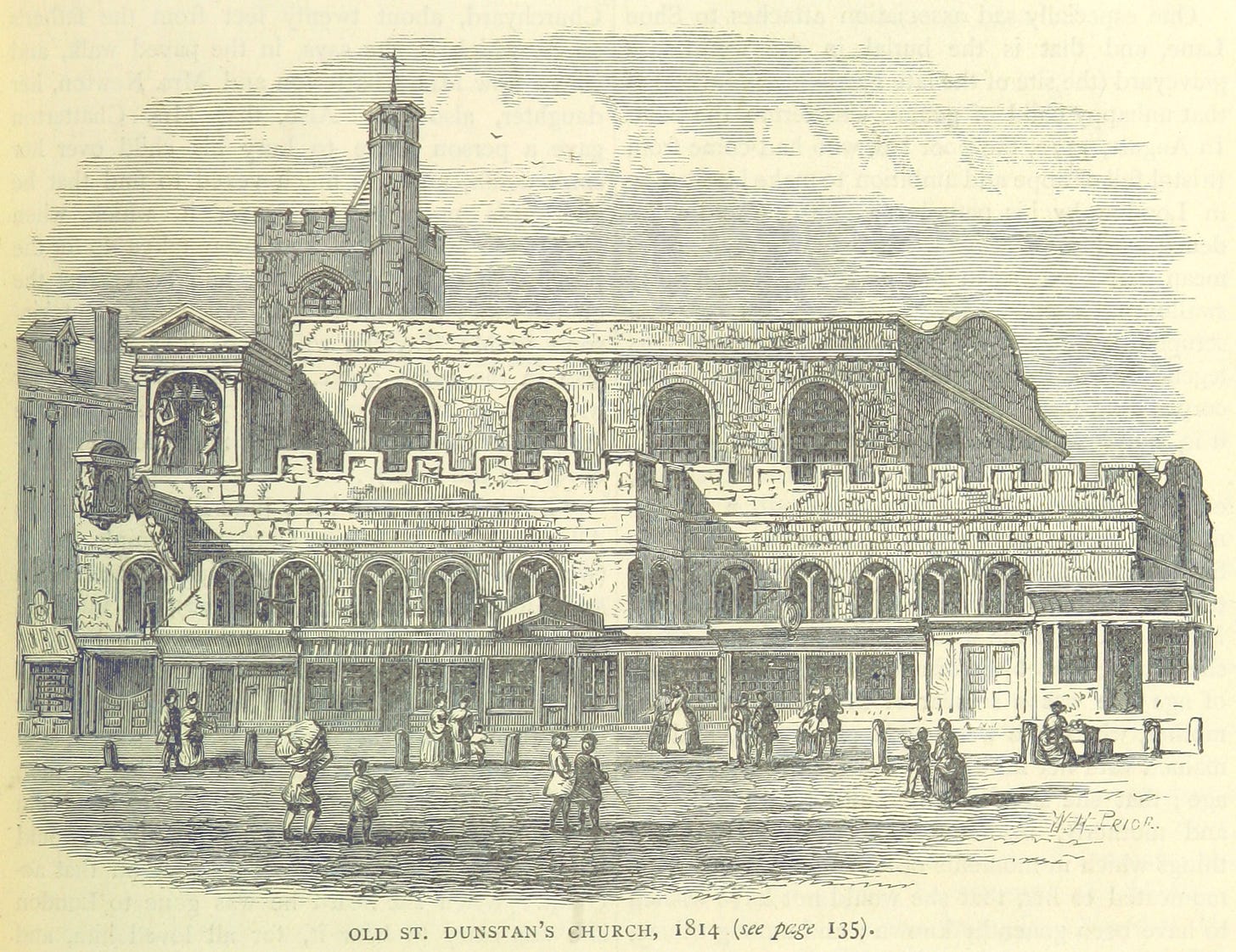

There were – and still are – two churches of St. Dunstan in London, St. Dunstan-in-the-West and St. Dunstan-in-the-East. Dickens specifies that the church is on Fleet Street, so this is St. Dunstan-in-the-West, where the poet John Donne was vicar in the mid-seventeenth century, a few years before Mr. Pickwick’s story is set.

Incidentally, Dunstan was a Benedictine monk and Bishop of London in the 10th century. He’s best remembered for grabbing the Devil by the nose with a pair of tongs and nailing a horseshoe to his foot. St. Dunstan is now the patron saint of blacksmiths. Dickens references the legend in A Christmas Carol:

Piercing, searching, biting cold. If the good Saint Dunstan had but nipped the Evil Spirit’s nose with a touch of such weather as that, instead of using his familiar weapons, then indeed he would have roared to lusty purpose.

St. Dunstan’s is an interesting church for Dickens to choose, because it had been rebuilt only a few years before Master Humphrey’s Clock was published. The old church had escaped the Great Fire of London in 1666 – (thanks to forty boys from Westminster School, who dowsed the surrounding area in water) – but it was demolished in 1829 in order for Fleet Street to be widened.

The new church, which still stands, was completed in 1833, less than ten years before Dickens was writing. The current interior is remarkable – it’s octagonal – but the old interior, which Dickens was describing, and which George Cattermole illustrated, had disappeared.

The fact that the old church had recently been demolished, and was therefore fresh in the memory, may be why Dickens chose St. Dunstan-in-the-West for Mr. Pickwick’s story, but I have another theory.

If you look at the far left of the illustration of the old church above, you’ll see a large clock projecting from the building. This clock was installed in 1671 and was the first public clock in London to display a minute hand. You can still see the clock today outside St. Dunstan’s on Fleet Street.

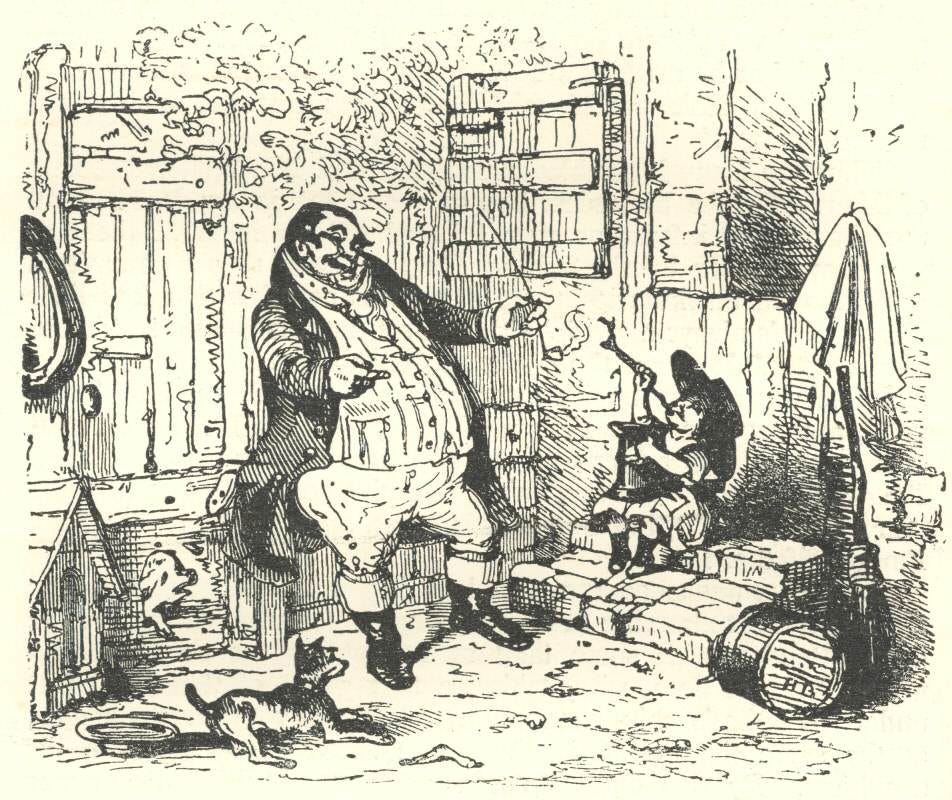

More interestingly, however, the clock has two statues of Gog and Magog, who strike the hours on bells with their clubs. When the church was demolished, the clock and statues were removed to Winfield House in Regent’s Park, where they remained until 1935, but Dickens certainly remembered them, because he includes a reference in Barnaby Rudge:

Hugh made no pause until Saint Dunstan’s giants struck the hour above him.

There’s no way of knowing, but I wonder if Dickens originally intended Mr. Pickwick’s story to be told by Gog and Magog – the giants from the first and second issues of Master Humphrey’s Clock – as one of their ‘legends of London . . . from the old simple times’. He certainly seemed to be setting them up as recurring narrators.

When he decided to introduce Mr. Pickwick as a character, perhaps he changed his mind and assigned the story to him instead, but the original association with Gog and Magog was still in his mind and suggested St. Dunstan’s as a location . . .

I look forward to the next instalment – including the second chapter of The Old Curiosity Shop – and to discussing it with you next Friday!

Here are links to our previous Old Curiosity Shop posts:

The Schedule (14 March 2025)

Charles Dickens (28 March)

0. Forster’s Life of Dickens (4 April)

1. Master Humphrey’s Clock No.1 – and Gog and Magog (11 April)

2. Master Humphrey’s Clock No.2 – and G. K. Chesterton (18 April)

3. Master Humphrey’s Clock No.3 – and Edgar Allan Poe (25 April)

4. Master Humphrey’s Clock No.4 – and the Old Curiosity Shop (2 May)

And if you’re not reading The Old Curiosity Shop with us, remember you can choose to opt out of our conversation. Just follow this link to your settings and, under Notifications, slide the toggle next to ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’. A grey toggle means you will not receive emails relating to this title.

That’s an interesting theory about Gog and Magog being the original intended narrators for this section. Dickens’s creative process in cobbling these stories together really fascinates me, and it seems that, even six weeks in, he still didn’t have a clear idea where he was going with Master Humphrey.

I was expecting some kind of deflation or joke in the second part of the story involving what actually was going on. The twist here is intriguing — the spy ends up doing a more noble or “Christian” thing (albeit for money) than the exposure of “witches.” At the end he needs to reinforce the hysteria and superstition of witch hunting rather than expose it for the sham that it was. It’s as if society needs to preserve its delusions at all cost. I’m reminded of the orphan workhouse in Oliver Twist and the school in Nicholas Nickleby — institutions that harm to individuals are covered up by societal delusions of doing good.