Read-along – The Old Curiosity Shop (5 of 18)

Master Humphrey's Clock No.5 – and Mr. Pickwick

Dear Old Curiosity Shop readers,

We’ve read the fifth issue of Master Humphrey’s Clock – which featured the surprise appearance of Mr. Pickwick – what did you think? Please do share your thoughts in the comments below. Here are my impressions:

Here are the details of the next instalment:

No.6 (9 May)

There were two items in the sixth issue of Master Humphrey’s Clock:

– ‘Second Chapter of Mr. Pickwick’s Tale’

– ‘Further Particulars of Master Humphrey’s Visitor’

(If you don’t have a physical copy of Master Humphrey’s Clock you can find these sections online here. Stop before ‘The Clock’.)

In case you’re unfamiliar with Mr. Pickwick, here’s a quick primer:

In 1836, Charles Dickens – whose ‘Sketches by Boz’ had already proved popular – was invited by the publishers Chapman and Hall to write texts to accompany a series of ‘cockney sporting prints’ by the artist Robert Seymour.

The result was The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, an enormously popular novel consisting of the loosely connected comic adventures of Samuel Pickwick, founder and perpetual president of ‘The Pickwick Club’, and his hapless friends, the inept poet Augustus Snodgrass, the ineffectual lover Tracy Tupman and the incompetent sportsman Nathaniel Winkle.

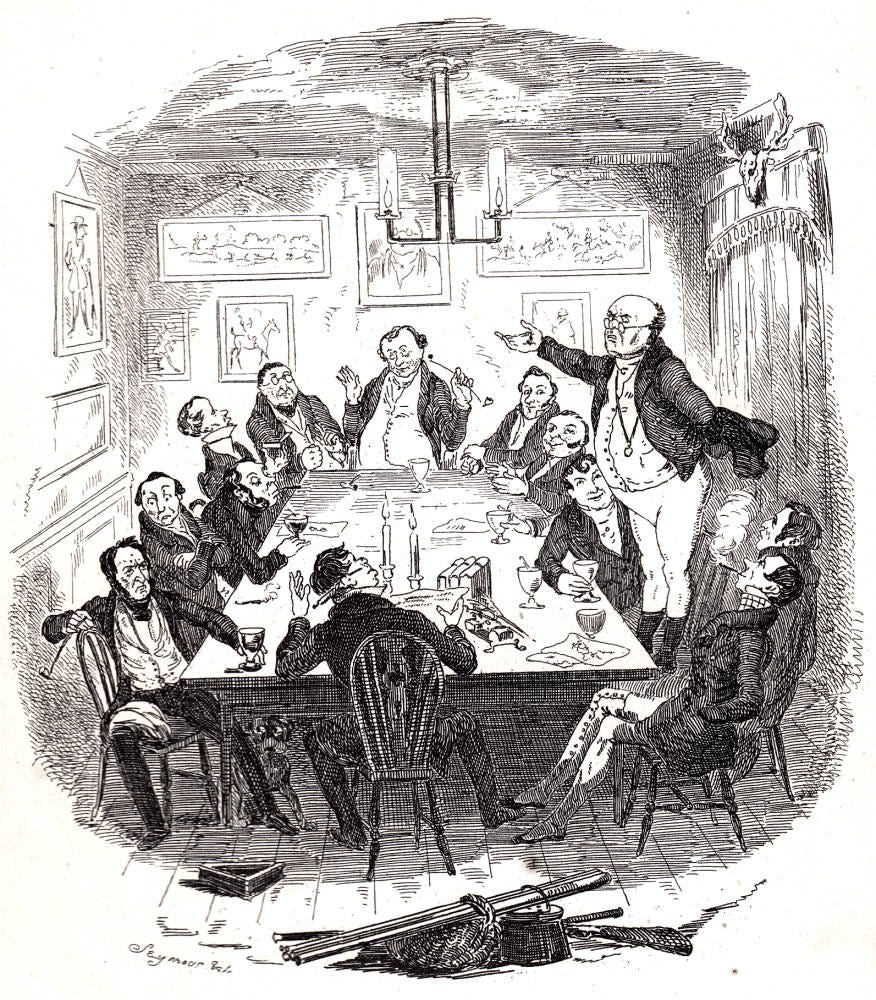

Here is Mr. Pickwick’s first appearance in the opening instalment:

A casual observer might possibly have remarked nothing extraordinary in the bald head, and circular spectacles, which were intently turned towards his (the secretary’s) face, during the reading of the above resolutions: to those who knew that the gigantic brain of Pickwick was working beneath that forehead, and that the beaming eyes of Pickwick were twinkling behind those glasses, the sight was indeed an interesting one. There sat the man who had traced to their source the mighty ponds of Hampstead, and agitated the scientific world with his Theory of Tittlebats, as calm and unmoved as the deep waters of the one on a frosty day, or as a solitary specimen of the other in the inmost recesses of an earthen jar. And how much more interesting did the spectacle become, when, starting into full life and animation, as a simultaneous call for ‘Pickwick’ burst from his followers, that illustrious man slowly mounted into the Windsor chair, on which he had been previously seated, and addressed the club himself had founded. What a study for an artist did that exciting scene present! The eloquent Pickwick, with one hand gracefully concealed behind his coat tails, and the other waving in air to assist his glowing declamation; his elevated position revealing those tights and gaiters, which, had they clothed an ordinary man, might have passed without observation, but which, when Pickwick clothed them—if we may use the expression—inspired involuntary awe and respect; surrounded by the men who had volunteered to share the perils of his travels, and who were destined to participate in the glories of his discoveries.

Even more popular than Mr. Pickwick, however, was his long-suffering, wise-cracking servant, assistant and loyal friend, Samuel Weller, who was introduced in the fourth instalment of The Pickwick Papers and turned a popular series into a publishing phenomenon. Sam’s popularity led to a flurry of merchandise, including a Sam Weller ‘jest book’ containing more than 1,000 jokes, puns, epigrams and jeux d’esprit.

‘One of my life’s greatest tragedies,’ said the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, ‘is to have already read Pickwick Papers – I can’t go back and read it for the first time.’

G. K. Chesterton points out that the only time Dickens ever resurrected one of his fictional characters was this instance of Mr. Pickwick returning in Master Humphrey’s Clock.

We have already read some of G. K. Chesterton’s essay in our discussion of the second issue of Master Humphrey’s Clock. Here is what he says about Pickwick:

The ordinary reader can remember one great thing about Master Humphrey’s Clock, besides the fact that it was the frame-work of The Old Curiosity Shop. He remembers that Mr. Pickwick and the Wellers rise again from the dead. Dickens makes Samuel Pickwick become a member of Master Humphrey’s Clock Society; and he institutes a parallel society in the kitchen under the name of Mr. Weller’s Watch.

Before we consider the question of whether Dickens was wise when he did this, it is worth remarking how really odd it is that this is the only place where he did it. Dickens, one would have thought, was the one man who might naturally have introduced old characters into new stories. Dickens, as a matter of fact, was almost the one man who never did it. It would have seemed natural in him for a double reason; first, that his characters were very valuable to him, and second that they were not very valuable to his particular stories. They were dear to him, and they are dear to us; but they really might as well have turned up (within reason) in one environment as well as in another. We, I am sure, should be delighted to meet Mr. Mantalini in the story of Dombey and Son. And he certainly would not be much missed from the plot of Nicholas Nickleby. ‘I am an affectionate father,’ said Dickens, ‘to all the children of my fancy; but like many other parents I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child; and his name is David Copperfield.’ Yet although his heart must often have yearned backwards to the children of his fancy whose tale was already told, yet he never touched one of them again even with the point of his pen. The characters in David Copperfield, as in all the others, were dead for him after he had done the book; if he loved them as children, it was as dead and sanctified children. It is a curious test of the strength and even reticence that underlay the seeming exuberance of Dickens, that he never did yield at all to exactly that indiscretion or act of sentimentalism which would seem most natural to his emotions and his art. Or rather he never did yield to it except here in this one case; the case of Master Humphrey’s Clock.

And it must be remembered that nearly everybody else did yield to it. Especially did those writers who are commonly counted Dickens’s superiors in art and exactitude and closeness to connected reality. Thackeray wallowed in it; Anthony Trollope lived on it. Those modern artists who pride themselves most on the separation and unity of a work of art have indulged in it often; thus, for instance, Stevenson gave a glimpse of Alan Breck in The Master of Ballantrae, and meant to give a glimpse of the Master of Ballantrae in another unwritten tale called The Rising Sun. The habit of revising old characters is so strong in Thackeray that Vanity Fair, Pendennis, The Newcomes, and Philip are in one sense all one novel. Certainly the reader sometimes forgets which one of them he is reading. Afterwards he cannot remember whether the best description of Lord Steyne’s red whiskers or Mr. Wagg’s rude jokes occurred in Vanity Fair, or Pendennis; he cannot remember whether his favourite dialogue between Mr. and Mrs. Pendennis occurred in The Newcomes, or in Philip. Whenever two Thackeray characters in two Thackeray novels could by any possibility have been contemporary, Thackeray delights to connect them. He makes Major Pendennis nod to Dr. Firmin, and Colonel Newcome ask Major Dobbin to dinner. Whenever two characters could not possibly have been contemporary he goes out of his way to make one the remote ancestor of the other. Thus he created the great house of Warrington solely to connect a ‘blue-bearded’ Bohemian journalist with the blood of Henry Esmond. It is quite impossible to conceive Dickens keeping up this elaborate connection between all his characters and all his books, especially across the ages. It would give us a kind of shock if we learnt from Dickens that Major Bagstock was the nephew of Mr. Chester. Still less can we imagine Dickens carrying on an almost systematic family chronicle as was in some sense done by Trollope. There must be some reason for such a paradox; for in itself it is a very curious one. The writers who wrote carefully were always putting, as it were, after-words and appendices to their already finished portraits; the man who did splendid and flamboyant but faulty portraits never attempted to touch them up. Or rather (we may say again) he attempted it once, and then he failed.

The reason lay, I think, in the very genius of Dickens’s creation. The child he bore of his soul quitted him when his term was passed like a veritable child born of the body. It was independent of him, as a child is of its parents. It had become dead to him even in becoming alive. When Thackeray studied Pendennis or Lord Steyne he was studying something outside himself, and therefore something that might come nearer and nearer. But when Dickens brought forth Sam Weller or Pickwick he was creating something that had once been inside himself and therefore when once created could only go further and further away. It may seem a strange thing to say of such laughable characters and of so lively an author, yet I say it quite seriously; I think it possible that there arose between Dickens and his characters that strange and almost supernatural shyness that arises often between parents and children; because they are too close to each other to be open with each other. Too much hot and high emotion had gone to the creation of one of his great figures for it to be possible for him without embarrassment ever to speak with it again. This is the thing which some fools call fickleness; but which is not the death of feeling, but rather its dreadful perpetuation; this shyness is the final seal of strong sentiment; this coldness is an eternal constancy.

This one case where Dickens broke through his rule was not such a success as to tempt him in any case to try the thing again.

There is weakness in the strict sense of the word in this particular reappearance of Samuel Pickwick and Samuel Weller. In the original Pickwick Papers Dickens had with quite remarkable delicacy and vividness contrived to suggest a certain fundamental sturdiness and spirit in that corpulent and complacent old gentleman. Mr. Pickwick was a mild man, a respectable man, a placid man; but he was very decidedly a man. He could denounce his enemies and fight for his nightcap. He was fat; but he had a backbone. In Master Humphrey’s Clock the backbone seems somehow to be broken; his good nature seems limp instead of alert. He gushes out of his good heart; instead of taking a good heart for granted as a part of any decent gentleman’s furniture as did the older and stronger Pickwick. The truth is, I think, that Mr. Pickwick in complete repose loses some part of the whole point of his existence. The quality which makes the Pickwick Papers one of the greatest of human fairy tales is a quality which all the great fairy tales possess, and which marks them out from most modern writing. A modern novelist generally endeavours to make his story interesting, by making his hero odd. The most typical modern books are those in which the central figure is himself or herself an exception, a cripple, a courtesan, a lunatic, a swindler, or a person of the most perverse temperament. Such stories, for instance, are Sir Richard Calmady, Dodo, Quisante, La Bête Humaine, even the Egoist. But in a fairy tale the boy sees all the wonders of fairyland because he is an ordinary boy. In the same way Mr. Samuel Pickwick sees an extraordinary England because he is an ordinary old gentleman. He does not see things through the rosy spectacles of the modern optimist or the green-smoked spectacles of the pessimist; he sees it through the crystal glasses of his own innocence. One must see the world clearly even in order to see its wildest poetry. One must see it sanely even in order to see that it is insane.

Mr. Pickwick, then, relieved against a background of heavy kindliness and quiet club life does not seem to be quite the same heroic figure as Mr. Pickwick relieved against a background of the fighting police constables at Ipswich or the roaring mobs of Eatanswill.

I look forward to the next instalment – and the conclusion of Mr. Pickwick’s tale – and to discussing it with you next Friday!

Here are links to our previous Old Curiosity Shop posts:

The Schedule (14 March 2025)

Charles Dickens (28 March)

0. Forster’s Life of Dickens (4 April)

1. Master Humphrey’s Clock No.1 – and Gog and Magog (11 April)

2. Master Humphrey’s Clock No.2 – and G. K. Chesterton (18 April)

3. Master Humphrey’s Clock No.3 – and Edgar Allan Poe (25 April)

4. Master Humphrey’s Clock No.4 – and the Old Curiosity Shop (2 May)

And if you’re not reading The Old Curiosity Shop with us, remember you can choose to opt out of our conversation. Just follow this link to your settings and, under Notifications, slide the toggle next to ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’. A grey toggle means you will not receive emails relating to this title.

I think Charles Dickens knew something about media, fear mongering and how the public love giving into propaganda - “for people like to be frightened, and when they can be frightened for nothing and at another man’s expense, they like it all the better.” I did not know people gathered around fires to read to each other in those times though. We need more of that to be honest.

My favorite part of this week's installment is the treatment of Mr Pickwick as a huge celebrity. Master Humphrey is bristling with energy through the whole episode. I hadn't thought there'd be so much similarity between 19th century London and our current celebrity culture. Dickens was a huge celebrity himself, of course, and he seems to take delight in sending up the fawning and the hero worship.

Master Humphrey is comically accomodating; he is gloriously low-status in the presence of a celebrated figure. I've lived for years in NYC and L.A., so I've had my share of celebrity sightings, as I'm sure the London members of our group have. So I laughed at the level of detail of practically every word, thought, and action of both Master Humphrey and Mr Pickwick in this scene. Decades later, I still recount -- in minute detail to absolutely anyone -- passing such-and-such a celebrity on the street or watching someone eat their meal in a restaurant. And not just what they were wearing but what *I* was wearing in their presence.

I disagree a bit with Chesterton's assessment of Pickwick as weaker or softer here. I think we're seeing Pickwick from Master Humphrey's perspective, and Master Humphrey sees a kind, generous celebrity who has unexpectedly favored him. And we can be sure Master Humphrey will tell any passing acquaintance all about this first encounter for the rest of his life.