Read-along – The Counterfeiters (6 of 6)

Part Three, Chapters 14-20 – and Forster's paraboloid egg

Dear Counterfeiters,

We’ve finished The Counterfeiters! What did you think? Please do share your thoughts in a comment below. Here are mine:

The Counterfeiters was partially inspired by two separate news stories about schoolboys, which Gide hoped to combine into a plot. He saved the newspaper clippings and used them while he was writing.

Here is an extract from the start of his Journal of The Counterfeiters:

16 July 1919

This morning I took out once again the various newspaper clippings concerning the case of the counterfeiters. I am sorry not to have saved more of them. They are from the Journal de Rouen (Sept. 1906). I think I shall have to begin from there without trying any longer to construct a priori. . . . Essential to connect this to the case of the anarchist counterfeiters of 7 and 8 August 1907 – and to the sinister account of the schoolboys’ suicides at Clermont-Ferrand (5 June 1909). Weld this into a single homogenous plot.

As an appendix to his journal, he reprinted two of these clippings. Here is the first:

Figaro, 16 September 1906

They operated in the following manner:

The counterfeit coins were manufactured in Spain, introduced into France, and brought by three professional criminals: Djl, Monnet, and Tornet. They were delivered to the middlemen Fichat, Micornet, and Armanet and sold by them for 2 fr. 50 each to the youths who were to pass them on.

These latter were bohemians, second-years students, unemployed journalists, artists, novelists, etc. But there was in addition a certain number of young students from the École des Beaux-Arts, several sons of public officials, the son of a provincial magistrate, and a minor employee of the Ministry of Finance. [. . .]

If for some of them this criminal trade was a means of leading a ‘high life’ beyond that permitted by their family allowance, for others – at least according to them – it was a humanitarian work: ‘Once in a while I would give a few to poor devils with money troubles who could use them to keep their families alive. . . . And nobody was harmed, because we were stealing from nobody by the State.’

And the second:

Journal de Rouen, 5 June 1909

SUICIDE OF A SCHOOLBOY

We have noted the dramatic suicide of young Nény, barely fifteen years old, who, in the middle of a class at the Lycée Blaise-Pascal at Clermont-Ferrand, blew out his brains with a revolver.

The Journal des Débats has received from Cermont-Ferrand the following strange details:

‘That an unfortunate child, raised in a family where there took place scenes of such violence that often – in fact, on the very eve of his death – he was obliged to go to stay with neighbours, should have been led to the idea of suicide is regrettable, but understandable. That assiduous and uncontrolled reading of pessimistic German philosophers should have led him to an ill-conceived mysticism, “his personal religion,” as he said, is also understandable. But that there should have been, in this large city school, an evil society of youngsters for forcing one another to suicide is monstrous; but unfortunately this must be admitted to be the case.

‘Is is said that three of these schoolboys drew lots to determine which would kill himself first. It is certain, however, that the unhappy Nény’s two accomplices in a sense forced him to end his days by accusing him of cowardice, and that on the previous day they made him go through a complete rehearsal of this heinous act, marking with a chalk X on the floor the place where he was to blow our his brains the next day. A pupil who entered at this moment saw this rehearsal: he was flung out the door with the threat: “You know too much – we’ll have to take care of you” – there was, it seems, a list of those who were to be taken care of.

‘It is established moreover that, ten minutes before the final scene, the boy next to Nény borrowed a watch from a pupil and told Nény: “You know you are to kill yourself at three twenty; you have only ten – five – two minutes!” At the time specified, the victim got up, stood at the spot marked with the chalk, took out his revolver, and fired it into his right temple. It is also true that when he fell, one of the conspirators had the horrible presence of mind to leap for the revolver and spirit it away. it has not yet been recovered. What will be done with it next? The whole thing is an atrocity: the pupils’ parents are emotionally at the breaking-point, as can well be imagined!’

Five years later, as Gide was finalising his novel, writing the closing chapters, he made the following entry in his journal:

Cuverville, 27 July 1924

Boris. The poor child realizes that there is not one of his qualities, not one of his virtues, that his companions cannot turn into a shortcoming: his chastity into impotence, his sobriety into absence of appetite, his general abstinence into cowardice, his sensitiveness into weakness. Just as there are no bonds like shortcomings or vices held in common, likewise nobility of soul prevents easy acceptance (being accepted as well as accepting).

The death of Boris makes for a shocking and tragic climax to The Counterfeiters.

Ironically, in the novel’s final chapter – another extract from Edouard’s journal – Edouard, Gide’s alter ego, writes that he ‘shall not make use of little Boris’s suicide for my Counterfeiters; I have too much trouble understanding it.’

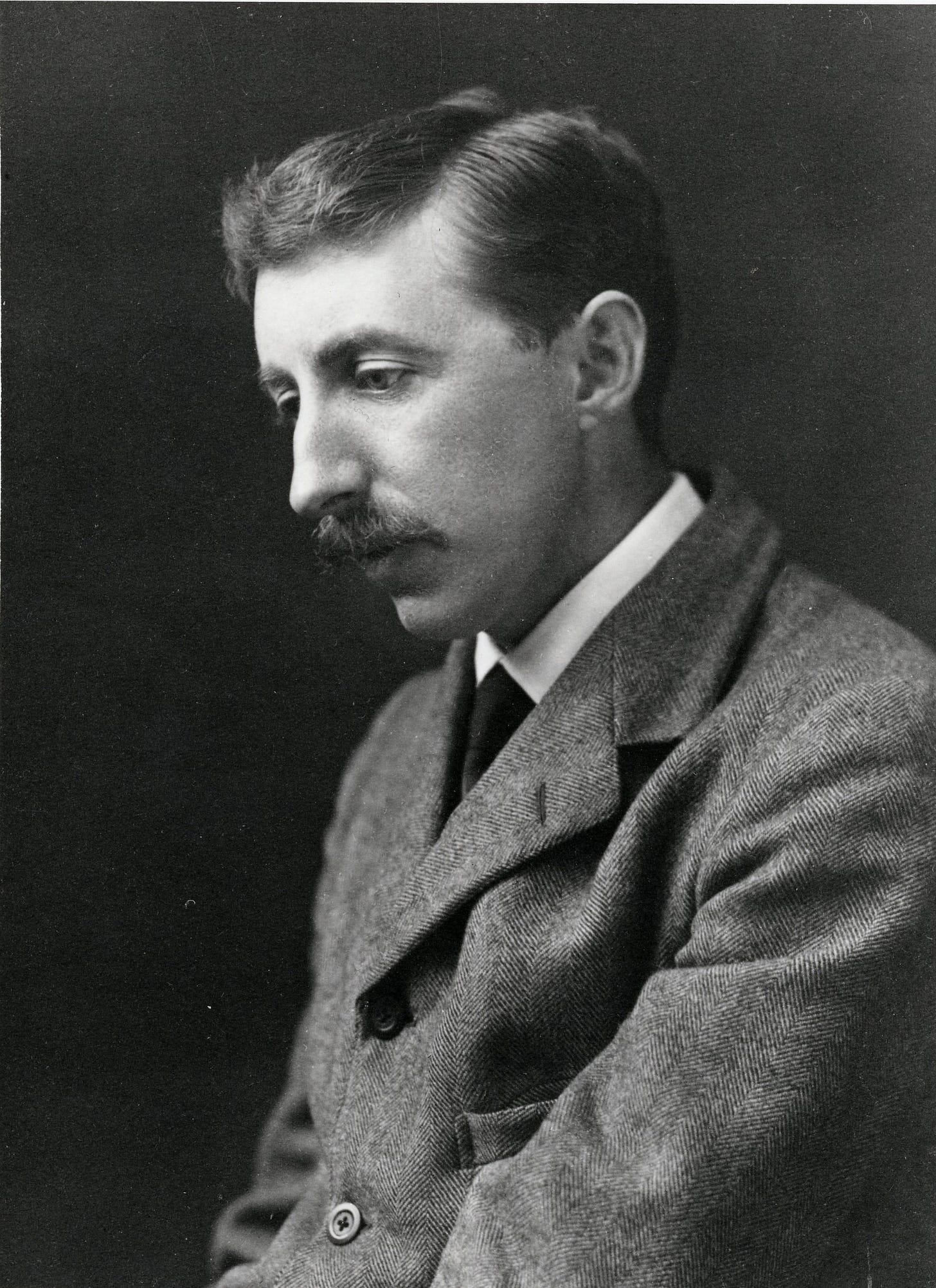

Which brings me on to E. M. Forster’s analysis of The Counterfeiters in his Aspects of the Novel (1927).

Forster’s conclusion is that Gide is too self-conscious in these metatextual moments:

The novelist who betrays too much interest in his own method can never be more than interesting; he has given up the creation of character and summoned us to help analyse his own mind, and a heavy drop in the emotional thermometer results. Les Faux Monnayeurs is among the more interesting of recent works: not among the vital: and greatly as we shall have to admire it as a fabric we cannot praise it unrestrictedly now.

And in his chapter on ‘Plot’ Forster really tackles Gide’s method:

We will now examine a recent example—a violent onslaught on the plot as we have defined it: a constructive attempt to put something in the place of the plot.

I have already mentioned the novel in question: Les Faux Monnayeurs by André Gide. . . . We have, in the first place, a plot in Les Faux Monnayeurs of the logical objective type that we have been considering—a plot, or rather fragments of plots. The main fragment concerns a young man called Olivier—a charming, touching and lovable character, who misses happiness, and then recovers it after an excellently contrived dénouement; confers it also; this fragment has a wonderful radiance and ‘lives,’ if I may use so coarse a word, it is a successful creation on familiar lines. But it is by no means the centre of the book. No more are the other logical fragments—that which concerns Georges, Olivier’s schoolboy brother, who passes false coin, and is instrumental in driving a fellow-pupil to suicide. (Gide gives us his sources for all this in his diary, he got the idea of Georges from a boy whom he caught trying to steal a book off a stall, the gang of coiners were caught at Rouen, and the suicide of children took place at Clermont-Ferrand, etc.) Neither Olivier, nor Georges, nor Vincent a third brother, nor Bernard their friend is the centre of the book. We come nearer to it in Edouard. Edouard is a novelist. He bears the same relation to Gide as Clissold does to Wells. I dare not be more precise. Like Gide, he keeps a diary, like Gide he is writing a book called Les Faux Monnayeurs, and like Clissold he is disavowed. Edouard’s diary is printed in full. It begins before the plot-fragments, continues during them, and forms the bulk of Gide’s book. Edouard is not just a chronicler. He is an actor too; indeed it is he who rescues Olivier and is rescued by him; we leave those two in happiness.

But that is still not the centre. The nearest to the centre lies in a discussion about the art of the novel. [See our discussion of Part II, Chapter 3.] This passage is the centre of the book. It contains the old thesis of truth in life versus truth in art, and illustrates it very neatly by the arrival of an actual false coin. What is new in it is the attempt to combine the two truths, the proposal that writers should mix themselves up in their material and be rolled over and over by it; they should not try to subdue any longer, they should hope to be subdued, to be carried away. As for a plot—to pot with the plot, break it up, boil it down. Let there be those ‘formidable erosions of contour’ of which Nietzsche speaks. All that is prearranged is false.

Another distinguished critic has agreed with Gide—that old lady in the anecdote who was accused by her nieces of being illogical. For some time she could not be brought to understand what logic was, and when she grasped its true nature she was not so much angry as contemptuous. ‘Logic! Good gracious! What rubbish!’ she exclaimed. ‘How can I tell what I think till I see what I say?’ Her nieces, educated young women, thought that she was passée; she was really more up to date than they were.

Those who are in touch with contemporary France, say that the present generation follows the advice of Gide and the old lady and resolutely hurls itself into confusion, and indeed admires English novelists on the ground that they so seldom succeed in what they attempt. Compliments are always delightful, but this particular one is a bit of a backhander. It is like trying to lay an egg and being told you have produced a paraboloid—more curious than gratifying. And what results when you try to lay a paraboloid, I cannot conceive—perhaps the death of the hen. That seems the danger in Gide’s position—he sets out to lay a paraboloid; he is not well advised, if he wants to write subconscious novels, to reason so lucidly and patiently about the subconscious; he is introducing mysticism at the wrong stage of the process. However that is his affair. As a critic he is most stimulating, and the various bundles of words he has called Les Faux Monnayeurs will be enjoyed by all who cannot tell what they think till they see what they say, or who weary of the tyranny by the plot and of its alternative, tyranny by characters.

It’s been a pleasure reading The Counterfeiters with you.

Please do join me for another classic read-along! On Wednesday this week we will be reading Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway in real-time over a single day – and next month we’ll be reading Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe over four weeks.

Here are links to our previous The Counterfeiters posts:

The Schedule (11 April)

André Gide (21 April)

0. Le Jardin du Luxembourg (2 May)

2. Part One, Chapters 10-18 – and Cocteau’s reviews (16 May)

3. Part Two, Chapters 1-7 – and Edouard’s Theory of the Novel (23 May)

4. Part Three, Chapters 1-6 – and the Butterfly of Parnassus (30 May)

I really didn’t like this one. It was just too weird!

Perhaps it is better in French.

But I enjoyed exposure to this novelist who won the Nobel prize in his day.