Dear classics readers,

This July we have some unconventional plots (The Stone Door and The Employee), unconventional memoirs (I Remember and Memoir of a Good-for-Nothing), unconventional relationships (Chinatown and Engagement) and two poignant portraits of mental illness (The Ha-Ha and I Am Clarence).

I Remember by Joe Brainard (1970)

Brainard’s method was brilliantly simple: to set down specific memories as they rose to the surface of his consciousness, each beginning with the refrain ‘I remember’: ‘I remember that little jerk you give just before you fall asleep. Like falling.’ Recollections – jokes, confessions, daydreams and memories – were carefully, lovingly woven together. They were of family and friends; of movie stars; of early heterosexual fumblings and later gay life. Brainard’s pared-back prose dodged both self-pity and judgement of others, and was written with an ear for musical cadence and an extraordinary painter’s eye. The result is witty, incantatory, profound and wholly captivating.

[UK:] Daunt Books | 208 pages | introduced by Paul Auster and Olivia Laing

[US:] Granary Books | 196 pages | introduced by Ron Padgett

The Stone Door by Leonora Carrington (1977)

The Stone Door is an omen, an incantation, and an adventure story rolled into one. Built in layers like a puzzle box, it is the tale of two people, of love and the Zodiac and the Kabbalah, of Transylvania and Mesopotamia converging at the Caucasus, of a mad Hungarian King named Böles Kilary and of a woman’s discovery of an initiatory code that leads to a Cyclopean obstacle, to love, self and awareness, to the great stone door of Kescke and beyond.

[UK / US:] NYRB Classics | 136 pages | introduced by Gabriel Weisz Carrington

The Ha-Ha by Jennifer Dawson (1961)

A tea party at an Oxford college. Earnest undergraduates in floral dresses clink cups, discussing essay-crises, punting, summer balls. But to one student, they are grotesquely transformed: she is sitting among ominous armadillos with scaly shells, buzzing with black flies. Then, the laughter comes. As she is engulfed by mirthless hysterics, the Principal has no choice but to send her away. Josephine’s entrance into the world of other people wasn’t what she imagined. Since her mother’s death, reality seems a badly painted canvas; she always thinks the wrong things, cowed by the brightness of existence. It is a relief to belong, for once, within the mental institution where she is taken. But eventually, she must reintegrate with society – and through a transformative encounter with a fellow patient, a return to real life seems possible.

[UK:] Faber Editions | 176 pages | introduced by Daisy Johnson

[US:] Scribner | 192 pages | introduced by Melissa Broder

Memoirs of a Good-for-Nothing by Joseph von Eichendorff (1826)

Eichendorff’s prose masterpiece – a picaresque account of the wanderings of a young man who leaves home after a row with his father, and who eventually finds love with the girl of his dreams – is one of the best-known classics of German literature. Deeply imbued with the style and sentiment of German Romanticism, and philosophical and poetic in its approach to nature and existence, Memoirs of a Good-for-Nothing is at once an exhilarating romp and a lively portrayal of nineteenth-century ideals.

[UK / US:] Alma Classics | 128 pages | translated by Ronald Taylor

I Am Clarence by Elaine Kraf (1969)

Clarence cannot see very well. He has seizures. He knows the word ‘tangerine’ but has forgotten the word ‘Mommy’. For Clarence’s mother, life revolves around her young son; she takes him to see specialists, protects him from the cruelty of other children, loves him fiercely. But she has her own struggles. Her sanity is precarious and fractured. When her mental health reaches breaking point, she is forced to decide between Clarence’s well-being and her own. Told through bright fragments of memories, I Am Clarence is a piercing journey into one woman’s mind, which asks, how much can a mother sacrifice for her child, and survive?

[UK:] Penguin Modern Classics | 224 pages | introduced by Sarah Manguso

[US:] Modern Library | 224 pages | introduced by Sarah Manguso

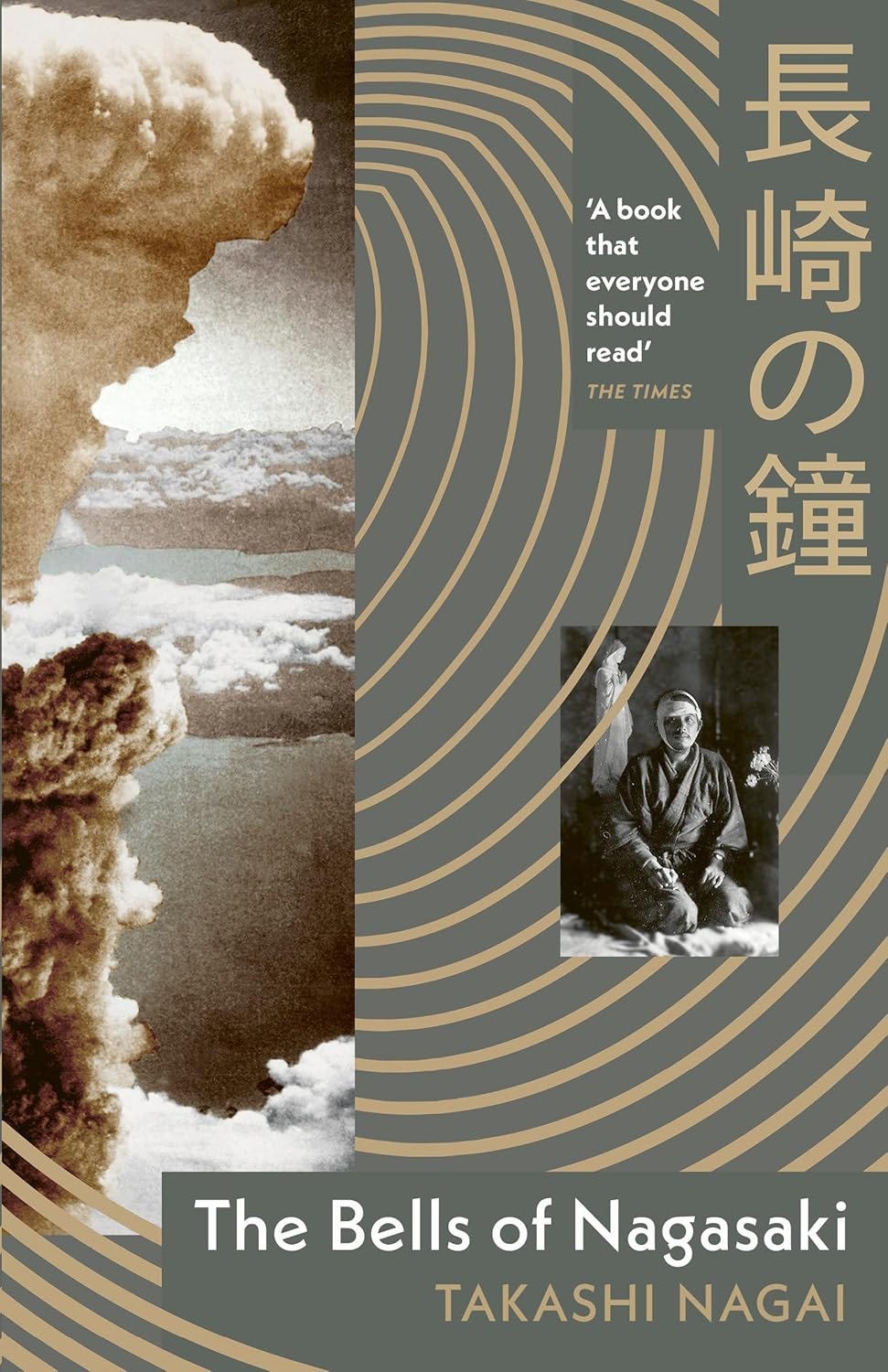

The Bells of Nagasaki by Takashi Nagai (1949)

On 9th August 1945, the Japanese city of Nagasaki is hit by an atomic bomb. Forty thousand people are killed instantly. Doctor Takashi Nagai is not one of them. Pulling himself, broken and bloodied, from the wreckage that was once the city’s university hospital, Takashi bundles together a tattered group of survivors. Doctors, nurses, students, each with their own losses, their own fears for the future: they work tirelessly at the impossible task of aiding the countless wounded and easing the deaths of those they cannot save. They remain determined to heal their fallen city, to find solace and hope among the rubble, even as a strange and growing sickness begins to claim them. Eyewitness to one of the most fatal events in human history, this is Takashi’s record, written from his sickbed – a chilling historical document, and undeniable evidence of the capacity for human kindness.

[UK:] Vintage Classics | 192 pages | translated by William Johnston | introduced by Richard Lloyd Parry

Chinatown by Oh Jung-hee (1960s-2020s)

In this emblematic selection of her stories, Oh Jung-hee probes beneath the surface of seemingly quotidian lives to expose nightmarish family configurations warped by desertion, psychosis, and death. In ‘Chinatown’ a young girl living on the edge of the city’s Chinese community comes of age among mundane violences, collisions with adult sexuality and the American occupation; in ‘The Garden Party’ a woman grapples with her conflicting identities of wife, mother and writer at an alcohol-fuelled gathering. Throughout a career spanning six decades, Oh Jung-hee has drawn comparisons to Alice Munro, Virginia Woolf, and Joyce Carol Oates, and is assuredly a trailblazing writer.

[UK:] Penguin Classics | 112 pages | translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton

Salt Water by Charles Simmons (1998)

It’s 1963, and fifteen-year-old Michael is spending the summer in the usual place: his family’s New England beach house. This isn’t a summer like the others, though. This is the summer he falls in love with the girl next door, twenty-year-old Zina. This is the summer he begins to understand the difference between what adults say and what they really mean. This is the summer he finds himself betrayed and learns in his turn to betray. This is the summer his life falls apart. This devastating coming-of-age story, inspired by Ivan Turgenev’s classic novel First Love, is a witty, elegiac masterpiece, which captures all the booze-soaked, salt-brined atmosphere of America’s last summer of innocence.

[UK:] Pushkin Press Classics | 192 pages | introduced by Vesna Goldsworthy

[US:] Gallery Books | 176 pages

The Employee by Jacques Sternberg (1958)

A nameless employee stands outside the door to an office, hesitating to enter because he is five minutes late. This banal opening then launches into a frenetic narrative that switches genres, modes and universes with abandon. From an account of his feral childhood with a nymphomaniacal mother, to his early development of a third arm and a second head, the employee unspools his subsequent life as department-store wrapper, ladder-descending bureaucrat, traveling salesman, murder suspect and other occupations. Years return and reverse through a series of inflicted hellscapes as a tension builds between an untrammeled imagination willing to commit any crime and the inescapable rigidity of the mind.

[UK / US:] Wakefield Press | 192 pages | translated by Matt Seidel

Engagement by Gun-Britt Sundström (1976)

Martina and Gustav, students in 1970s Stockholm, meet and fall immediately into coupledom. But what is coupledom? A route to marriage? A declaration of co-dependency? A new dimension of commitment and responsibility? A sexual confrontation? Or is it a habit that an intelligent person must consider breaking? Martina and Gustav discuss their relationship endlessly, between themselves and with others, as they try to make it work. Engagement, set during a time of social change and political upheaval, sees Martina trying to engage with the world on her own terms. Unwilling to marry, she finds herself in a state of permanent engagement while her friends settle down to marriage and children; uncertain of the world’s future, she engages with demos, sit-ins and philosophy seminars in her quest for a new blueprint for joy.

[UK:] Penguin Classics | 512 pages | translated by Kathy Saranpa

The book descriptions above are taken from the publishers’ online blurbs.

Buy a copy of any of the books above through Bookshop.org (UK) or Bookshop.org (US) and Read the Classics will earn a commission from your purchase. Thank you in advance for your support!

I send round-ups and recommendations like this on Mondays. If you’d prefer not to receive these emails – but you would like to receive our read-along messages – follow this link to your settings. Under Notifications slide the toggle next to ‘Read the Classics with Henry Eliot’. A grey toggle means you will not receive those emails.

Thanks for these round ups Henry - always something interesting to be found