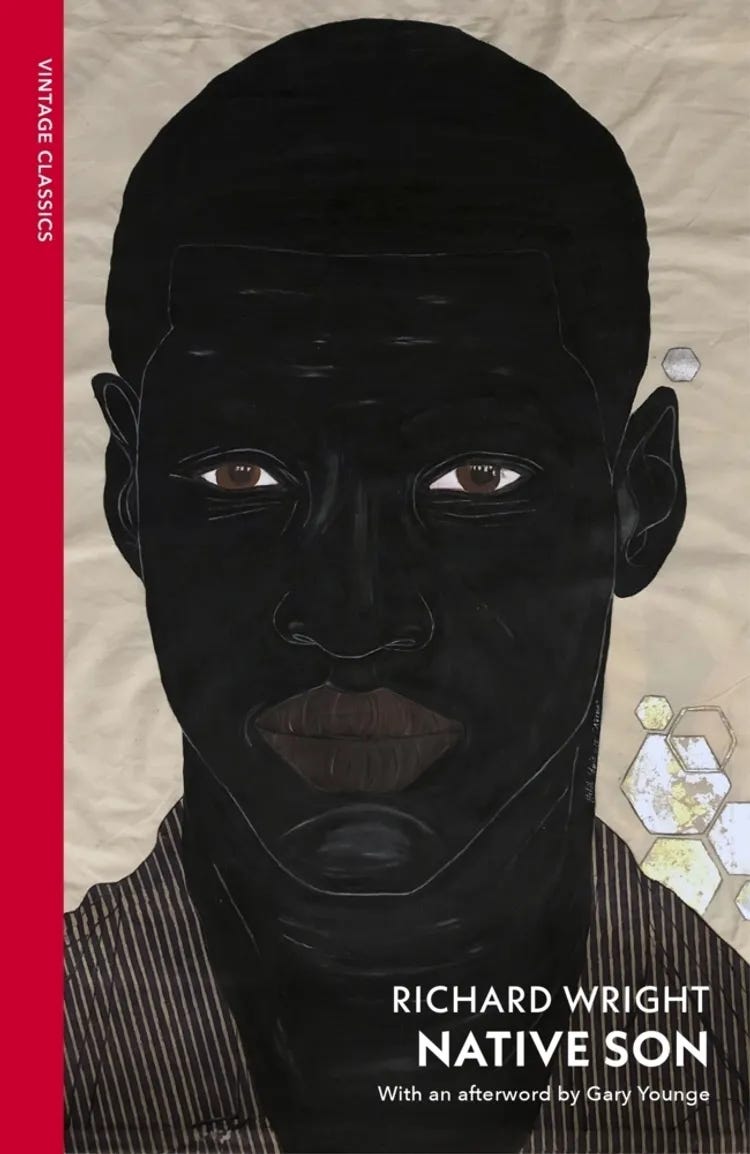

Native Son

by Richard Wright

October is Black History Month in the UK and Ireland. I recommend reading Richard Wright’s Native Son, one of the most influential African-American novels ever published.

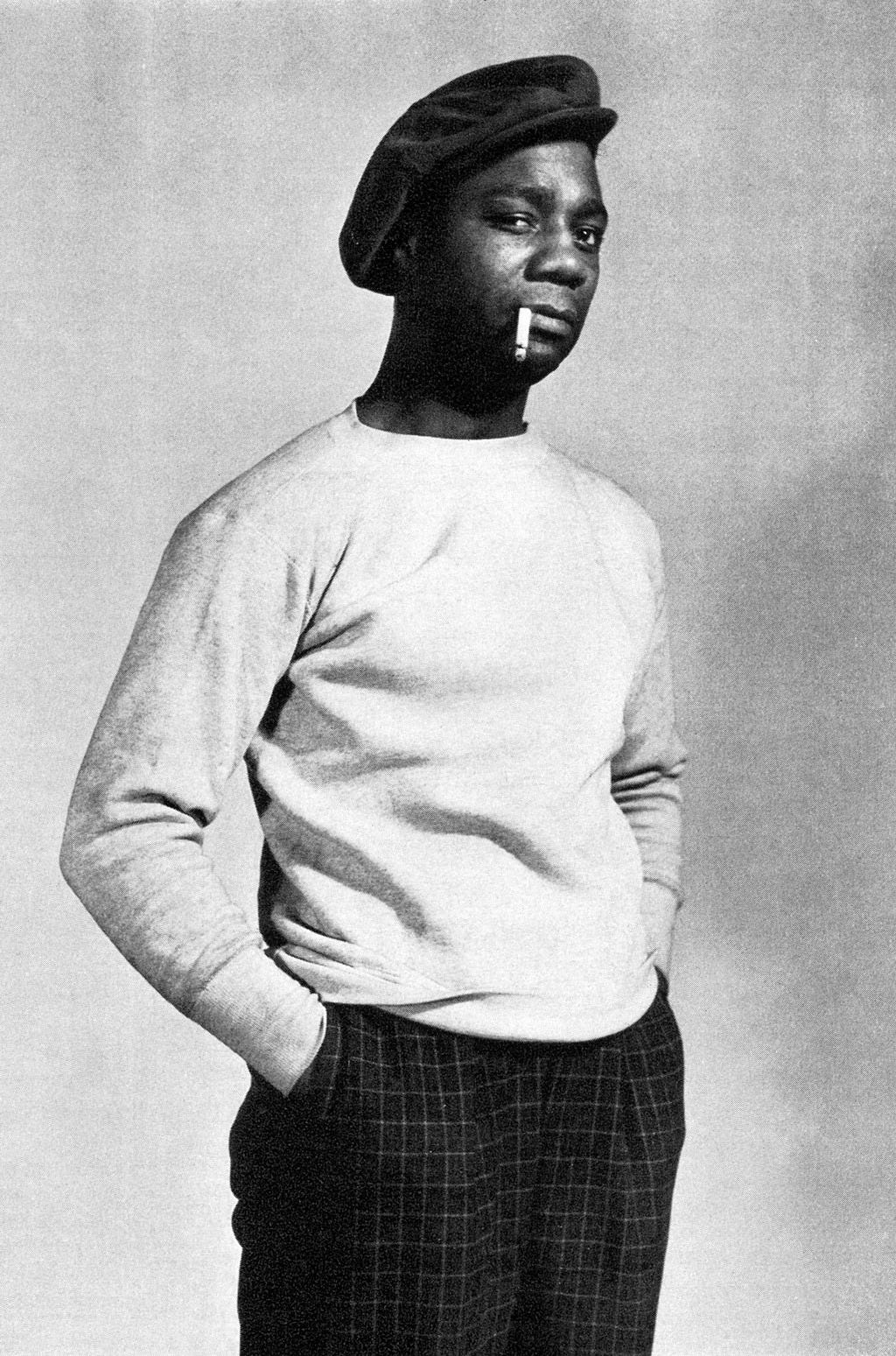

Wright was born in Roxie, Mississippi, the son of a sharecropper and a schoolteacher. He grew up with his maternal grandparents, strict Seventh-Day Adventists, who beat him frequently after he accidentally set their house on fire.

In 1927, he moved to Chicago, joined the Communist Party and began writing poetry and short stories. He became the Harlem editor of the Daily Worker in New York, and his volume of four short stories, Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), earned him a Guggenheim Fellowship that allowed him to complete his first novel, Native Son, in 1940.

With Native Son and his memoir, Black Boy (1945), Wright became a dominant voice of protest in the USA, laying bare the discrimination and injustice that African-Americans were experiencing.

In 1946, he moved with his wife and daughters to Paris, where he lived for the rest of his life. In Paris, he befriended the existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Albert Camus, whose philosophy influenced Wright’s second novel, The Outsider (1953).

He wrote eight novels in total, as well as stories, essays, plays and poetry. He died in November 1960 and is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Native Son tells the story of twenty-year-old Bigger Thomas, raised in Chicago’s deprived South Side in the 1930s. Product of a racist society, Bigger spirals into a desperate nightmare of violent crime and implacable punishment after accidentally killing a white woman.

‘The day Native Son appeared, American culture was changed forever,’ wrote the critic Irving Howe. ‘No matter how much qualifying the book might later need, it made impossible a repetition of the old lies.’

Native Son was the first Book-of-the-Month Club title by an African-American author. It sold 250,000 copies and was adapted in 1941 as a hit Broadway play, directed by Orson Welles.

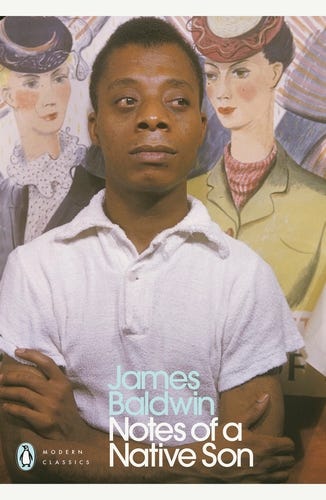

Native Son has inspired subsequent writers such as Maya Angelou, Lorraine Hansberry and Toni Morrison. No African-American exists, wrote James Baldwin, ‘who does not have his private Bigger Thomas living in his skull.’

Richard Wright became a mentor to the young James Baldwin when they were both living in New York. In 1948, Baldwin followed Wright to Paris, and Wright continued to support him, introducing him to literary contacts and finding him a room to live in.

Wright felt betrayed, however, when Baldwin published two essays about Native Son: ‘Everybody’s Protest Novel’ (1949) and ‘Many Thousands Gone’ (1951), both later collected in Baldwin’s landmark essay collection Notes of a Native Son (1955).

Baldwin praises Native Son as ‘the most powerful and celebrated statement we have yet had of what it means to be a Negro in America’, but he also seems to criticise the novel for being so dominated by ‘virtuous rage’ that it becomes a ‘continuation, a complement of that monstrous legend it was written to destroy’.

In large part, Baldwin was really justifying his own decision not to write a ‘protest’ novel himself, but sadly the essays destroyed his relationship with his mentor. Wright and Baldwin had a stormy scene in the Café Les Deux Magots in Saint-Germain-des-Prés and hardly spoke again.

After Wright died in 1960, Baldwin described him – in his essay ‘Alas, Poor Richard’ – as ‘the greatest black writer in the world to me’.

Buy a copy of Native Son through Bookshop.org and Read the Classics will earn a commission from your purchase. Thank you in advance for your support!

Thank you for this article. I have read and taught Native Son, and I have read Black Boy, as well. Now I want to read The Outsider. Just last month I was at Les Dieux Magots in Paris. I wish I had known about this Wright-Baldwin connection.

I love Wright's The Long Dream - read this as an undergrad and it stuck with me hard.