Dear Persuasion readers,

I’m really looking forward to our February read-along of Jane Austen’s last novel, Persuasion, which we will start next Friday 31 January. All the details are here.

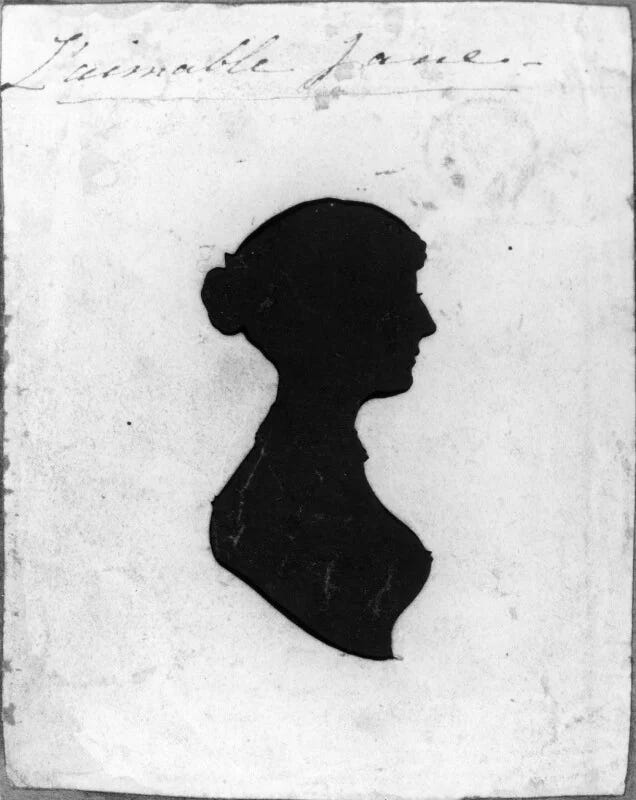

Here is a little about Austen’s life that might be useful before we get started.

Jane Austen was born 250 years ago on 16 December 1775, the seventh child of the Reverend George Austen, rector of the parish of Steventon in Hampshire. She attended schools in Oxford and Reading until the age of nine, after which she lived with her family for the rest of her life, educating herself through her own reading.

In December 1795, at the age of twenty, Austen met Tom Lefroy, a ‘very gentlemanlike, good-looking, pleasant young man’. They seem to have fallen in love – at least, Tom Lefroy’s family feared they might – because, rather like Captain Wentworth and Anne Elliot, they were forced apart in January 1796. That year Austen began writing a novel she called First Impressions, which would eventually be published as Pride and Prejudice.

George Austen retired in 1801 and the family moved to the city of Bath. In December 1802, when Austen was about to turn twenty-seven, she received her only known marriage proposal. Harris Bigg-Wither, a large, plain, tactless, stuttering heir to a local estate proposed to Jane and she accepted. She withdrew her acceptance the following morning.

In January 1805, George Austen died and Jane, her mother and her beloved older sister Cassandra were then supported by her brothers, James, Edward, Henry and Frank. When Edward inherited Chawton House in Hampshire, he gave his mother and sisters a cottage in the village. They arrived in July 1809 and Austen lived at Chawton for the last eight years of her life. All six of her novels were published while she lived there and the house is now the Jane Austen’s House Museum.

While living in Chawton, Jane’s only household responsibility was preparing breakfast for the family at nine o’clock and keeping the key to the wine cupboard. Otherwise she was allowed time to write.

In his not always reliable Memoir of Jane Austen, Austen’s nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh recalled how

She was careful that her occupation should not be suspected by servants, or visitors, or any persons beyond her own family party. She wrote upon small sheets of paper which could easily be put away, or covered with a piece of blotting paper. There was, between the front door and the offices, a swing door which creaked when it was opened; but she objected to having this little inconvenience remedied, because it gave her notice when anyone was coming.

Austen published four novels in her lifetime: Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814) and Emma (1815). Two others, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, the first and the last that she completed, were published posthumously in December 1817, just as she should have been celebrating her forty-second birthday. Austen died five months earlier in Winchester, while working on a new novel called Sanditon.

She was always modest about her own literary achievements, describing them as ‘the little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory, on which I work with so fine a Brush, as produces little effect after much labour’. The world, however, has chosen to disagree.

Henry James ranked Austen alongside Shakespeare, Cervantes and Fielding as one of ‘the fine painters of life’ and today she is the centre of a cult that has been growing since the 1880s. Obsessive ‘Janeites’ host Austen-themed reading groups, costumed teas, literary pilgrimages and weekend retreats.

In 2017 she replaced Charles Darwin on the British ten-pound note.

I look forward to talking more about Austen and to discussing her most romantic, most subtle and most mature novel, Persuasion, starting next week.

In other news, the Penguin Podcast released a bonus episode on Monday this week: seven minutes of extra material that didn’t make the final edit of my conversation with host Rhianna Dhillon. You can listen to the bonus episode here – and the original episode, first broadcast in October 2024, here.

And finally, a big thank you to everyone who joined me on Wednesday for our first classic film watch-along. We watched Safe (1995) by Todd Haynes – a fascinating movie in which Julianne Moore becomes increasingly ‘allergic to the 20th century’. She develops a debilitating sensitivity to chemicals that forces her to retreat gradually from friends, family and her home. Haynes tells the story in an unsettling way that raises more questions than it answers. It holds a disturbing and topical mirror up to modern life, cultish health fads, the stigma of illness and the artificial environments in which we live.

Next month we’ll be watching Brazil (1985) by Terry Gilliam on Wednesday 19 February – at 8pm UK time. The premiere of Brazil was held exactly 40 years ago, on Wednesday 20 February 1985. It’s a visually spectacular film that channels Kafka, Orwell, Monty Python and the Marx Brothers. I look forward to seeing you there!

If you’re not planning to read Persuasion with us, remember you can choose to opt out of our conversation. Just follow this link to your settings and, under Notifications, slide the toggle next to ‘Persuasion’. A grey toggle means you will not receive emails relating to this title.

Love, love, love Austen! She's my favorite author.