Gatsby turns 100

F. Scott Fitzgerald's American Dream

Dear classics readers,

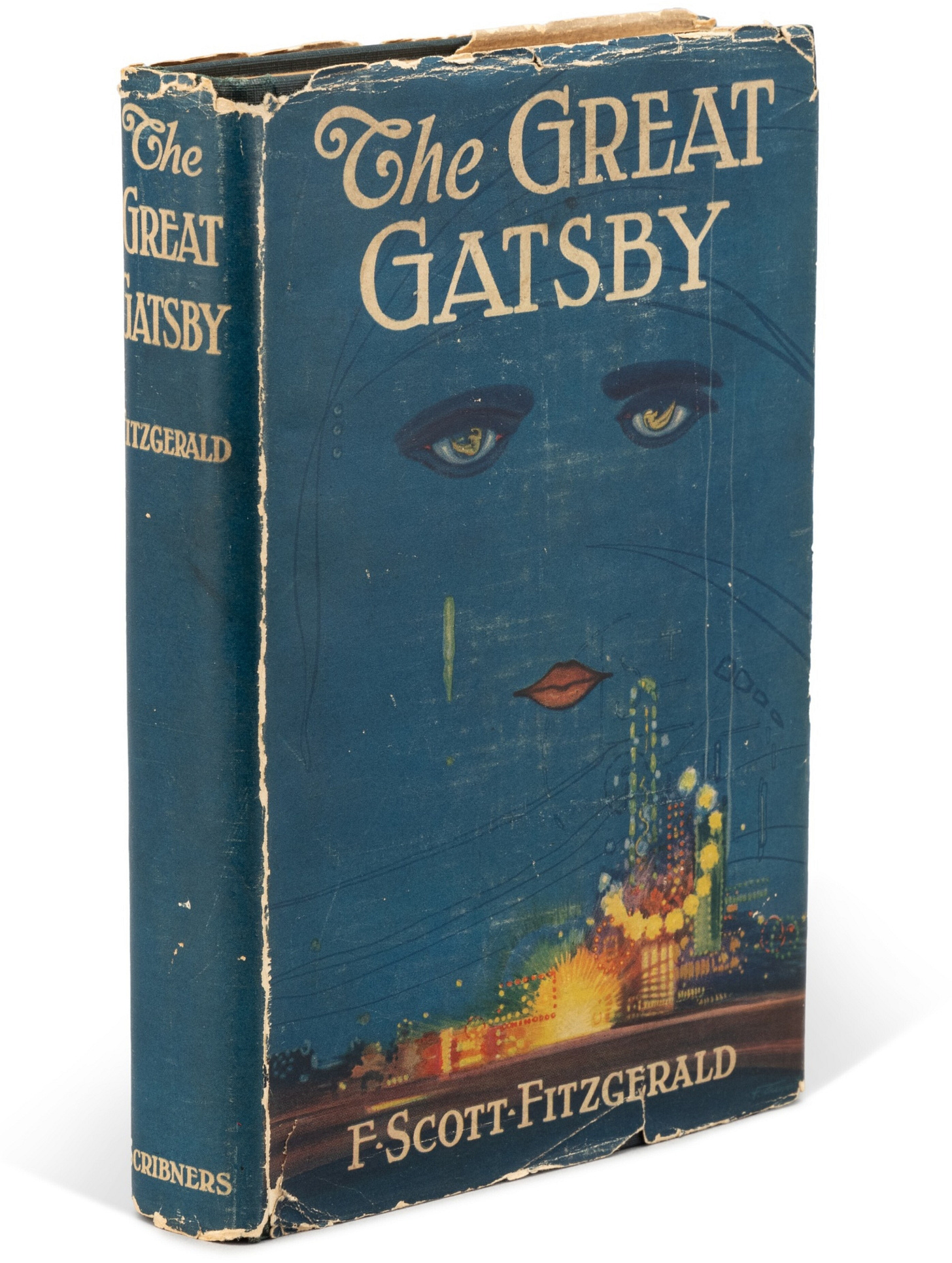

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby was published by Scribners in New York on 10 April 1925, exactly 100 years ago this Thursday.

The novel, now considered one of the greatest American novels of the twentieth century, was a commercial and critical disappointment when it first appeared – and Fitzgerald died thinking himself a failure and that his work was forgotten.

‘Poor son-of-a-bitch,’ Dorothy Parker is said to have muttered at his funeral, quoting The Great Gatsby.

The book’s lukewarm contemporary reception and posthumous acclaim may perhaps be explained by its prophetic qualities.

Although it is set during New York’s hedonistic Jazz Age – a term popularised and indeed exemplified by Fitzgerald himself – in hindsight its melancholy tone and doomed narrative appear to anticipate the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s.

One hundred years on, as America once again faces social and economic upheaval, the centenary of The Great Gatsby is a salutary opportunity to reread the novel and consider what it has to tell us about hope, truth and love.

In October 1925, a few months after The Great Gatsby was published, Fitzgerald wrote a letter to the critic Marya Mannes, in which he said:

America’s greatest promise is that something is going to happen, and after a while you get tired of waiting because nothing happens to people except that they grow old, and nothing happens to American art because America is the story of the moon that never rose.

At the core of The Great Gatsby is the idea of the ‘American Dream’, the consolatory but impossible myth that anyone can make a success of themselves in America, even if they’re ‘Mr Nobody from Nowhere’.

When Gatsby yearns towards the green light on Daisy’s dock, he expresses the same desperate optimism, its romance, its ambition and its futility. Fitzgerald compares Gatsby’s obsession to ‘following a grail’.

Fitzgerald expresses the inherently doomed nature of the dream most powerfully in the closing lines of the novel, a passage he had originally placed at the end of Chapter One, but which clearly belongs where it landed, as the book’s elegiac coda:

Most of the big shore places were closed now and there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferryboat across the Sound. And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes – a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms further . . . And one fine morning –

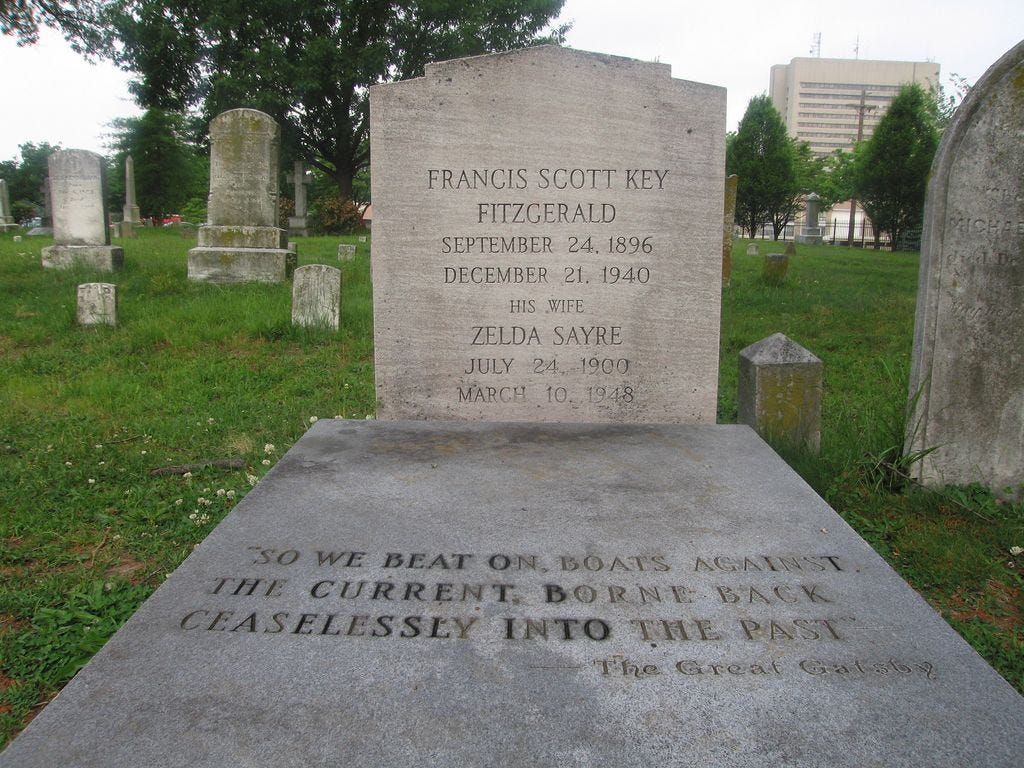

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

That beautiful last line is inscribed on the gravestone that Fitzgerald shares with his wife Zelda, one of the inspirations for Daisy in the novel.

Fitzgerald met the rich socialite Zelda Sayre while stationed in Alabama during the First World War. When the phenomenal success of his first two novels made him rich, they married in 1920, embarking on a non-stop spree of parties and hotels across America and then Europe. ‘I don’t want you to see me growing old and ugly,’ wrote Zelda. ‘We will just have to die when we’re thirty.’

Soon after The Great Gatsby was published, their marriage became increasingly marred by pathological alcoholism, suspected affairs and Zelda’s struggle with schizophrenia. Fitzgerald resorted to hack writing to support both their indulgent tastes and Zelda’s medical bills.

He died of a heart attack at the age of 44. Zelda spent her last years in a series of sanatoriums, increasingly violent and reclusive, until she died in a hospital fire at the age of 47.

Buy a copy of The Great Gatsby through Bookshop.org (UK) or Bookshop.org (US) and Read the Classics will earn a commission from your purchase. Thank you in advance for your support!

If you’re reading along with Anna Karenina or The Old Curiosity Shop I hope you’re enjoying it. On Friday we’ll be discussing the first issue of Dickens’s Master Humphrey’s Clock - and I’ll also be announcing our new May read-along!

Also, a reminder to paid subscribers that this Wednesday is our monthly Wednesday Watch-along, when we watch a classic film together at 8pm UK time. We’ll be watching the epic satire Underground by Emir Kusturica (1995) on its 30th anniversary. All the details are here.

And finally, I send recommendations and round-ups like this on Mondays. If you’d prefer not to receive these emails – but you would like to receive our read-along messages – follow this link to your settings. Under Notifications slide the toggle next to ‘Read the Classics with Henry Eliot’. A grey toggle means you will not receive those emails.

I love Gatsby. I know lots of people dismiss it, however, I find it to be hauntingly poignant. What always strikes me is Carraway’s disillusionment at the end of the novel when no one bothers to attend Gatsby’s funeral. All everyone was interested in was taking advantage of the free booze and entertainment - and no one cared about the man himself. It seems to foreshadow how Fitzgerald died without the appreciation and thanks for this brilliant novel - Perhaps there was a part of him that knew his ‘world’ was not ready, willing or able to recognise and understand the profundity of Gatsby’s story?!

I wish I could tell him that it worked out ok…

Thank you, Henry. What a wonderful essay. The Great Gatsby is my favorite American novel. For so many reasons. It is especially poignant to celebrate it now. The section you quoted here always has me in tears. Fitzgerald must have called to his muse when writing this. Only 208 pages in all~ but so poetic and timeless. It had never occurred to me that the reason it was not a success at the time was the prophesy it held. Fitzgerald was saying out loud what many must have known subconsciously about their lives. My grandmother came of age during the Jazz Age in New York City. She always seemed as if she had lost something. There is no other American novel that compares in capturing the loss of youthful promise, the squandering of gifts and the beauty of all that is unattainable.