Dear Robinsons,

I’m looking forward to our read-along of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, which we’re going to start on Friday 4th July next week. All the details are here.

First, though, here is a little about Daniel Defoe’s remarkable life and work.

Daniel Foe was born in London in 1660, the third son of a tallow chandler. As a child he survived the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666. (His house was one of only three in his area that didn’t burn down.)

His parents were Presbyterian dissenters and from the age of fourteen he attended Charles Morton’s dissenting academy in Newington Green. He most likely attended a dissenting church, at a time when anyone worshipping outside the Church of England would be persecuted.

As a young man he established himself as a hosier and general merchant on Cornhill, marrying his wife Mary Tuffley in 1684. The following year he joined the Duke of Monmouth’s rebellion against James II, which was a disaster. He was lucky to escape the ‘Bloody Assizes’ overseen by Judge Jeffreys.

Foe used his wife’s dowry to acquire a country estate, a ship and some perfume-producing civet cats, but he over-invested and when conflict with France affected foreign trade, he found himself in debt. He was arrested in 1692, declared bankrupt and sent to debtors’ prison.

On his release, he attempted various careers: selling wine in Portugal, working as a secret agent for King William III, collecting tax on glass bottles and making bricks in Essex. At about the same time he added the prefix ‘De’ to his name, making himself sound more aristocratic, and he turned his hand to writing.

His first success came with his satirical poem The True-Born Englishman (1701), a defence of William III, but public ignominy followed the publication of The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters (1702), which satirised High Anglican extremism and which led to his being publicly pilloried for three days. Legend has it that he was so popular among the crowd, they threw flowers instead of rotten vegetables.

Defoe wrote hundreds of books, pamphlets and poems. He wrote on topics ranging from politics to psychology, marriage and crime, but he is best remembered for his pioneering, genre-defining works of fiction. He wrote under an array of pseudonyms including ‘Andrew Moreton, Merchant’, ‘Eye Witness’, ‘T. Taylor’ and ‘Heliostrapolis, secretary to the Emperor of the Moon’.

Aside from his first novel, Robinson Crusoe (1719), which was a huge success, and to which he wrote two sequels, here are some of the Defoe’s other notable titles:

The Storm (1704)

On the evening of 26th November 1703, a cyclone from the north Atlantic hammered into southern Britain at over seventy miles an hour, claiming the lives of over 8,000 people. Eyewitnesses reported seeing cows left stranded in the branches of trees and windmills ablaze from the friction of their whirling sails. For Defoe, bankrupt and just released from prison for seditious writings, the storm struck during one of his bleakest moments. But it also furnished him with the material for his first book and what some call the first work of modern journalism.

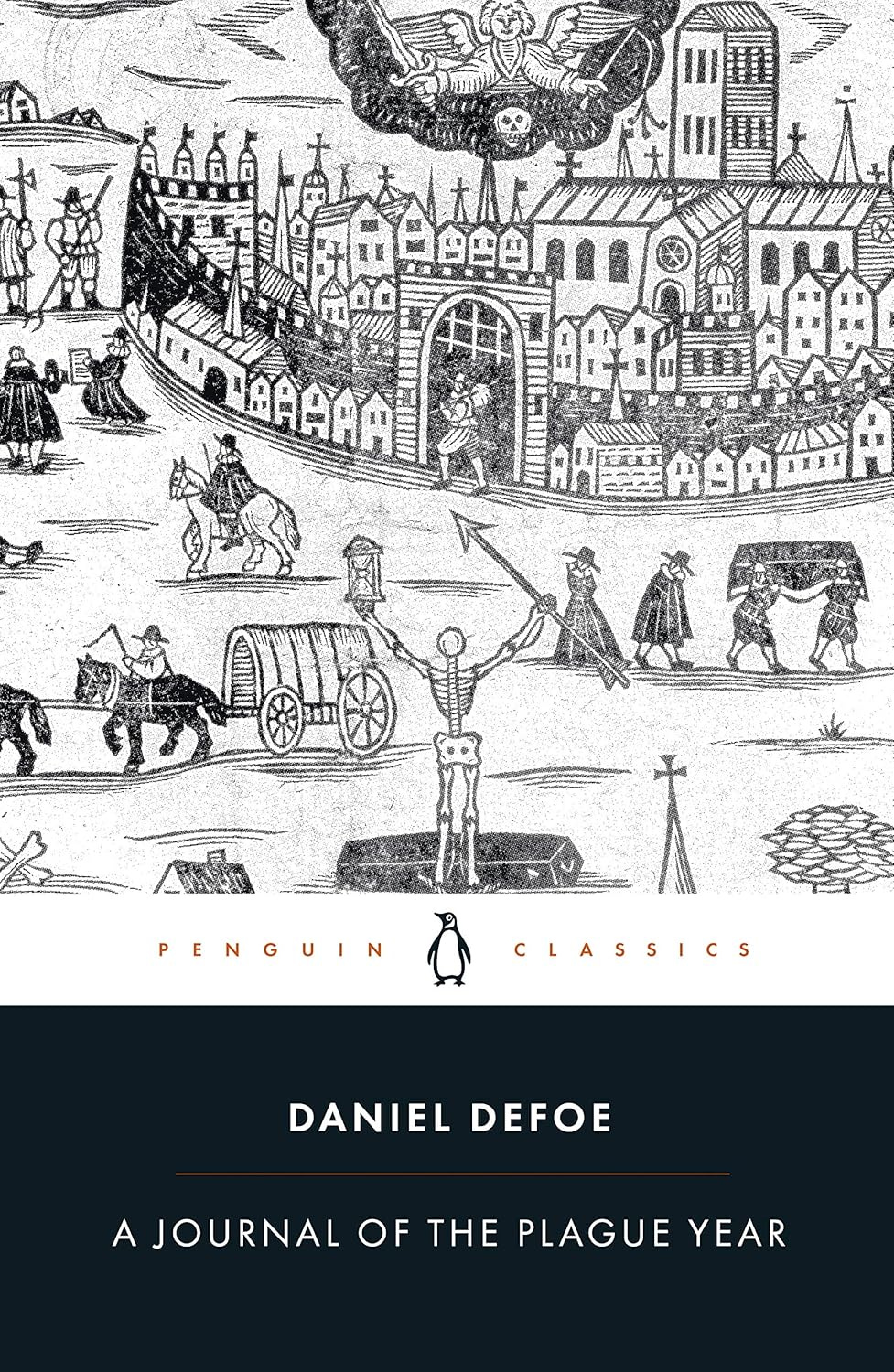

A Journal of the Plague Year (1722)

In 1665 the plague swept through London, claiming over 97,000 lives. Daniel Defoe was just five at the time of the plague, but he later called on his own memories, as well as his writing experience, to create this vivid chronicle of the epidemic and its victims. A Journal (1722) follows Defoe’s fictional narrator as he traces the devastating progress of the plague through the streets of London. Here we see a city transformed: some of its streets suspiciously empty, some – with crosses on their doors – overwhelmingly full of the sounds and smells of human suffering. And every living citizen he meets has a horrifying story that demands to be heard.

Colonel Jack (1722)

This novel begins among the alleyways of London and ends in the plantations of Virginia, providing a vivid recollection of a life of crime, marital disaster, political adventurism and penitent prosperity. The elusive hero, Colonel Jack, has been compared to Oliver Twist and Lucky Jim.

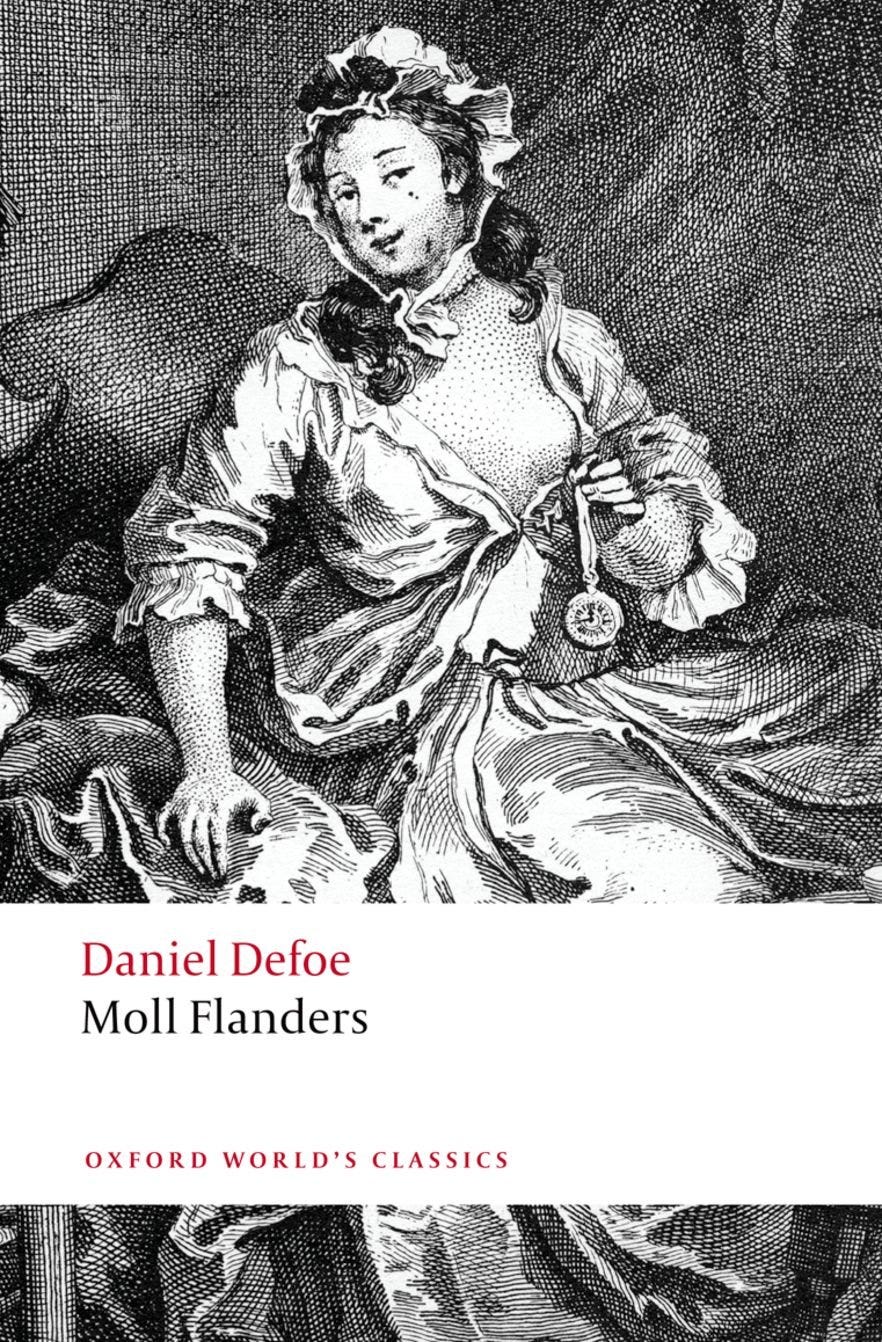

Moll Flanders (1722)

Twelve Year a Whore, fives times a Wife (whereof once to her own Brother), Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at last grew Rich, liv’d Honest, and died a Penitent

So the title page of this extraordinary novel describes the career of the woman known as Moll Flanders, whose real name we never discover. Moll tells her own story, a vivid and racy tale of a woman’s experience in the seamy side of life in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century England and America. Born in Newgate prison, and seduced in the home of her adoptive family, she learns to live off her wits, defying the traditional depiction of women as helpless victims.

The Fortunate Mistress, or Roxana (1724)

Left destitute by her husband, the heroine of Defoe’s final novel has to choose between her virtue and her life. Choosing survival, she makes her way as a kept woman and courtesan. The Fortunate Mistress (1724), also known under the title Roxana, tells the story of how she climbs society’s ladder by dint of her own enterprise, shedding and gaining multiple identities as she moves through the worlds of business and finance, and across the trade capitals of Europe. Amassing a fortune, her taste for men and luxuries veers increasingly to the aristocratic and exotic, culminating when she dances before the King at a masquerade dressed in the garb of a Turkish Sultana –at which point she is granted the name by which she is known to history, Roxana.

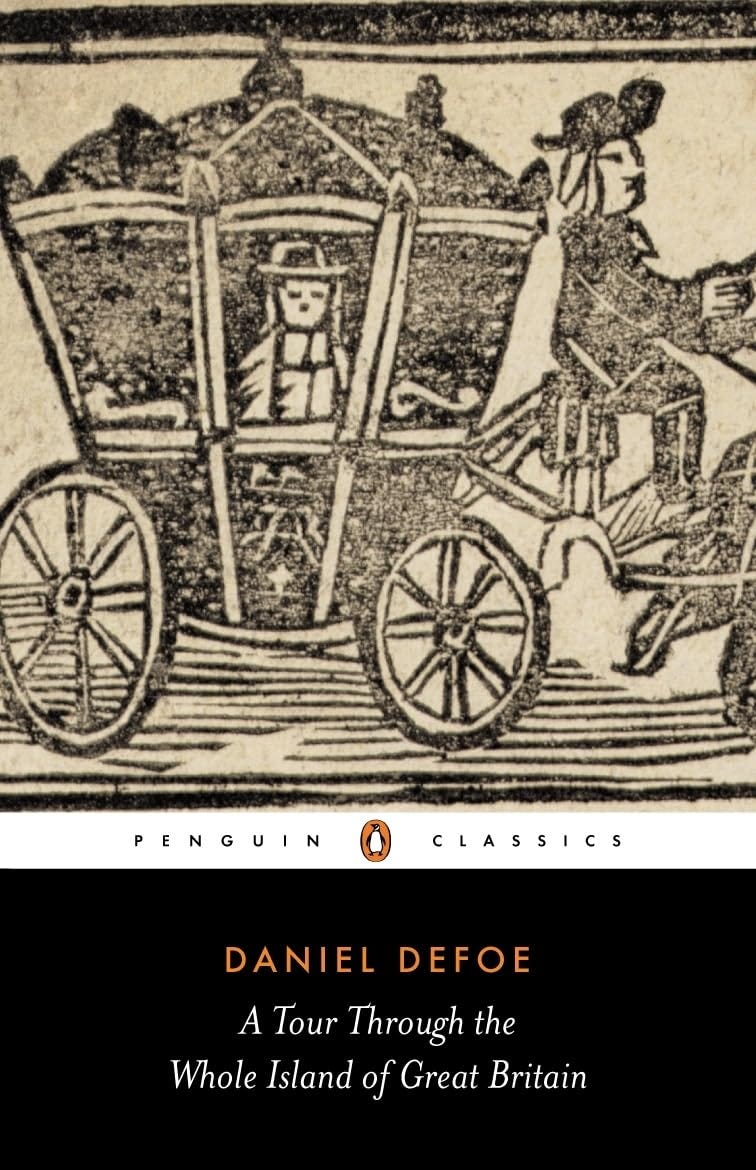

A Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-7)

Britain in the early eighteenth century: this is an introduction that is both informative and imaginative, reliable and entertaining. To the tradition of travel writing Daniel Defoe brings a lifetime’s experience as a businessman, soldier, economic journalist and spy, and his Tour (1724-6) is an invaluable source of social and economic history. But this book is far more than a beautifully written guide to Britain just before the industrial revolution, for Defoe possessed a wild, inventive streak that endows his work with astonishing energy and tension, and the Tour is his deeply imaginative response to a brave new economic world.

A Political History of the Devil (1726)

Defoe’s passionate and perceptive survey starts with Satan’s origins, chronicling the devil’s presence in the Bible and his growing sway over humanity. An overview of satanic influences on eighteenth-century life follows, focussing on monarchs and tyrants as well as common folk. Defoe supports his arguments not only with extensive quotes from scripture but also with citations from other sources, including Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Despite this prodigious output, Defoe never quite managed to escape from debt and in 1731 he died, hiding from his creditors on Ropemakers Alley, not far from where he was born in Cripplegate.

His cause of death was recorded as ‘lethargy’, which probably indicates a stroke.

He was buried in an unmarked grave in the dissenters’ burial ground, Bunhill Fields, a one-time plague cemetery outside London’s walls. It now boasts an obelisk in his memory, funded through public subscription by ‘the boys and girls of England’ in 1870.

I look forward to reading Defoe’s greatest achievement, Robinson Crusoe, with you, starting next Friday.

If you’re not planning to read Robinson Crusoe with us, you can choose to opt out of our conversation. Just follow this link to your settings and, under Notifications, slide the toggle next to ‘Robinson Crusoe’. A grey toggle means you will not receive emails relating to this title.

That is so interesting about Defoe’s life and his prolific output . That he still ends up penniless , but as a true adventurer who questioned and observed the times he lived in ..is amazing , rich and inspiring !

An excellent introduction to Daniel Defoe’s life and works - thank you for this, Henry! My appetite has definitely been whetted.